Darryl Sapien

Interviewed by Nick Kaye, San Francisco, 17 August 2015.

Follow the links for discussions of: In Transit (1971) | Chrysalis (1971) | Initiation (1972) | Diffusion Capsule (1972) | Portrait of the Artist x 3 (1979) | Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974) | Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975) | Splitting the Axis (1975) | A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art (1977) | Crime in the Streets (1978) | Hero (1980) | Pixellage (1983-84)

Why the step into performance?

I was 21 years old and I'd been working in sculpture. I started out as a painter but the school I was going to in southern California didn't have a sculpture department, they just had a painting department - it was a two-year Community College. When I came to the San Francisco Art Institute I decided I was going to get serious about doing sculpture. I started doing metal sculpture: welding. It was so laborious and time-consuming, and my ideas were so complicated it just took me forever to get anything done. On the other hand, when I finally did finish I was happy with the results. At the time I knew Howard Fried was doing performance art, but I wasn't really sure what he was doing. I went to see one of his shows at The Reese Palley Gallery and it was kind of confusing to me.

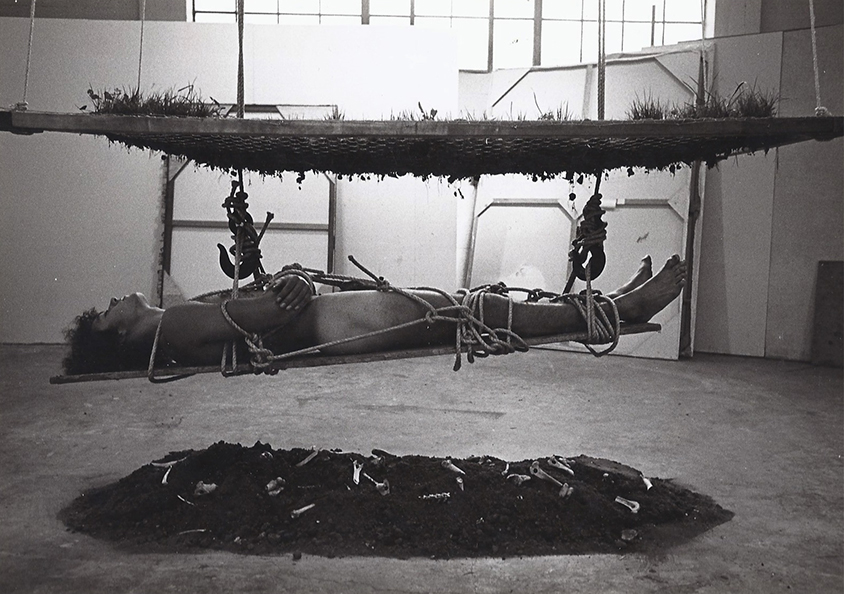

Darryl Sapien, In Transit (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, In Transit (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Which Fried show was that?

Oh, I don't know. It was 1971 I think. It was the one where he had Long John Silver and Long John Servil (1972) and Fuck You Purdue (1971). They were so inscrutable to me. I looked at the pictures: the pictures looked good, but I really wasn't clear on what he was trying to say. Then Tom Marioni had a show there, where he lived in the gallery [Tom Marioni, The Creation, a Seven Day Performance (Reese Palley Gallery, 1972)]. I thought that's an interesting idea. What really flipped the switch on for me was when I bought one of the first or second issues of Avalanche magazine - it was published by Willoughby Sharp out of New York. There was an article about Bruce Nauman and Terry Fox in there and it was all about performance art. I immediately got an idea for a performance that I would like to do. Just a year earlier I was in college in southern California and was participating in college level sports. I was playing football, American football, so the physicality of performance art really appealed to the athlete in me.

So this would have been in 1971?

Yeah. I left that college in February of '71. I was 20 years old when I arrived here in San Francisco. My good friend, Michael Hinton, who I ended up doing so many collaborations with, had already come up here to join the graduate painting department at the Art Institute. I'd come with him for his interview and decided I was going to go here too. I did sculpture at the Art Institute from February of '71 until June, then I went to San Diego to work that summer. All that summer I was working as a carpenter on these big apartment buildings. And I was thinking what I was doing in the moment has potential for a performance: just sawing rafter tails off and watching them drop and creating all these patterns on the ground. So then I came back and did a performance piece. I told myself, I'm going to do a performance, it's going to look a lot like work, but it's really a performance. And since then you could call a lot of my performance art pieces 'work' because the performative aspect of them is either building something, or tearing something apart, or putting it back together. There's always an aspect of labour involved.

Darryl Sapien, In Transit (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, In Transit (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

I'm aware of two pieces that you did at the Institute: In Transit (1971) and Diffusion Capsule (1972).

In Transit was a sculpture that I did using my body - the first piece I did when I got back to the Institute from San Diego in October. I suspended myself in mid-air, prone, lying on my back, tied with big ropes to a door, hanging from the ceiling. Above me was a screen of growing grass - below me was a mound of dirt with bones protruding out of it: so I was in transit between life and death. I was in a sort of meditative, self-induced comatose state for nearly eight hours.

I did another one at the Institute around this time, which was similar to that, but it was outside - Chrysalis (1971).

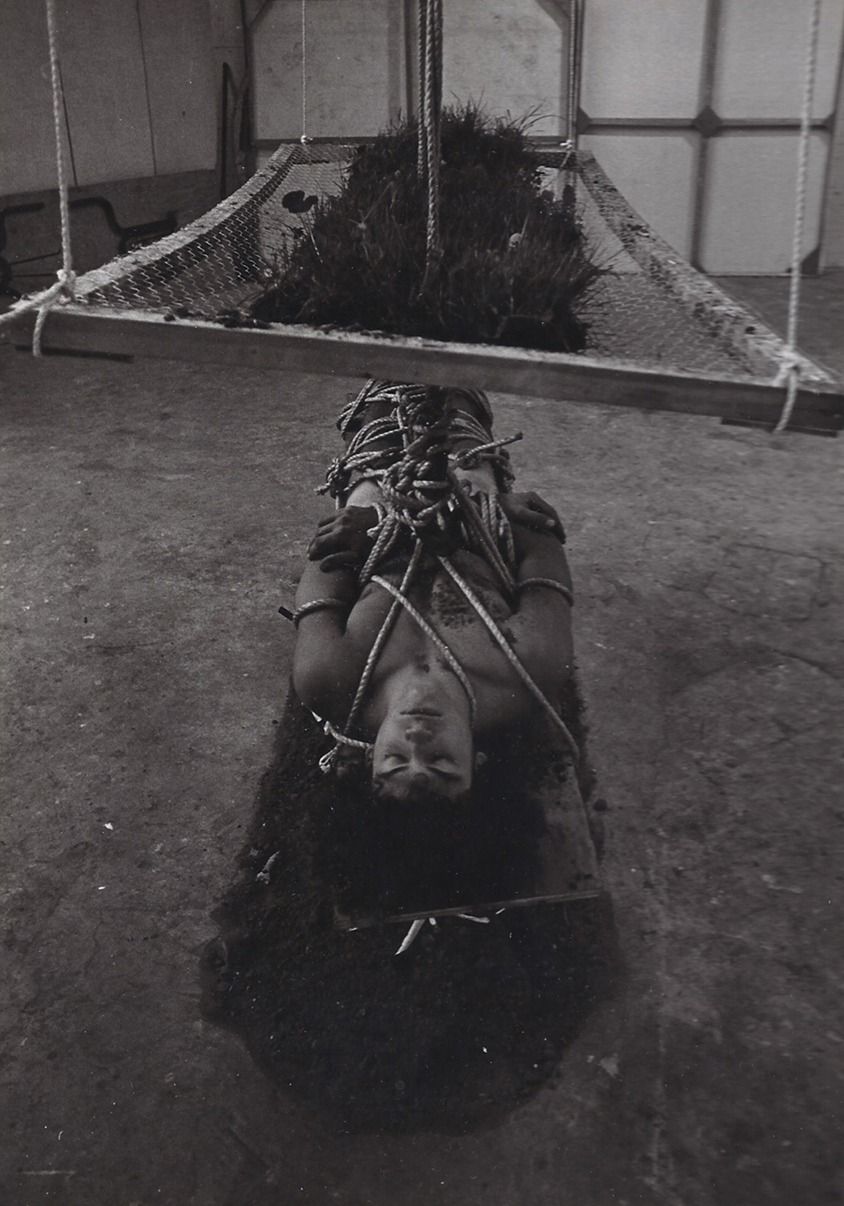

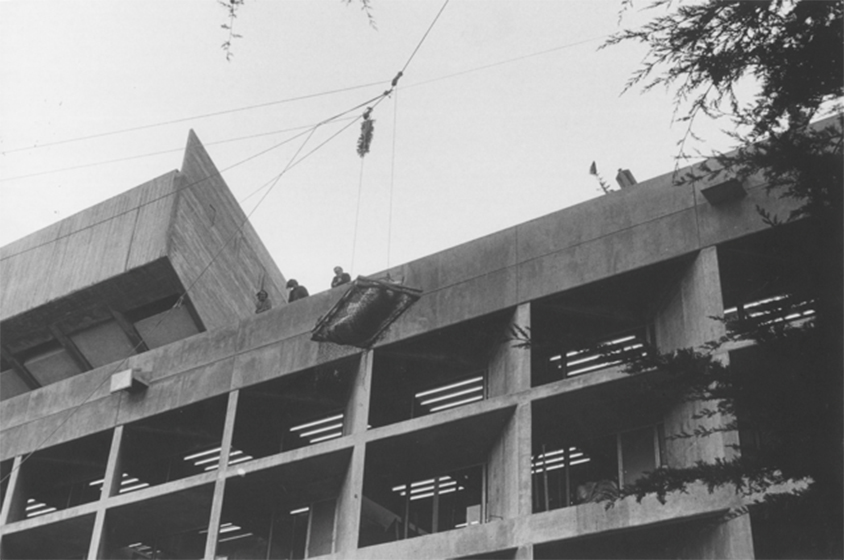

Darryl Sapien, Chrysalis (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Chrysalis (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

I had myself wrapped up in blankets, earplugs, blindfolded, tied up like Houdini; wrapped up in blankets, and then wrapped up in plastic, and put into sort of a net. It had a frame on it and I would lie there. I was there all day, for eight hours. It was outside in that big, empty field next to the Institute. I had tied ropes to the treetops, and one to the building, which made a cross in the air - then two pulleys attached to the ropes hoisted me up in the air so I was floating. I mean, quite high, like 30 feet up in the air - hanging there like some kind of a chrysalis undergoing a metamorphosis.

Darryl Sapien, Chrysalis (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Chrysalis (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Mostly I was just trying to transport myself into another state of consciousness and using my body as a purely sculptural object, as part of an outdoor sculpture piece. I didn't tell people I was going to do it. I just had assistants help me, wrap me up and put me in this net and then hoist me up and left me there for the whole day. People would come by and look at it - there was a rumour Darryl Sapien was in there. I wasn't moving, so people were throwing little rocks at me to see if I would move.

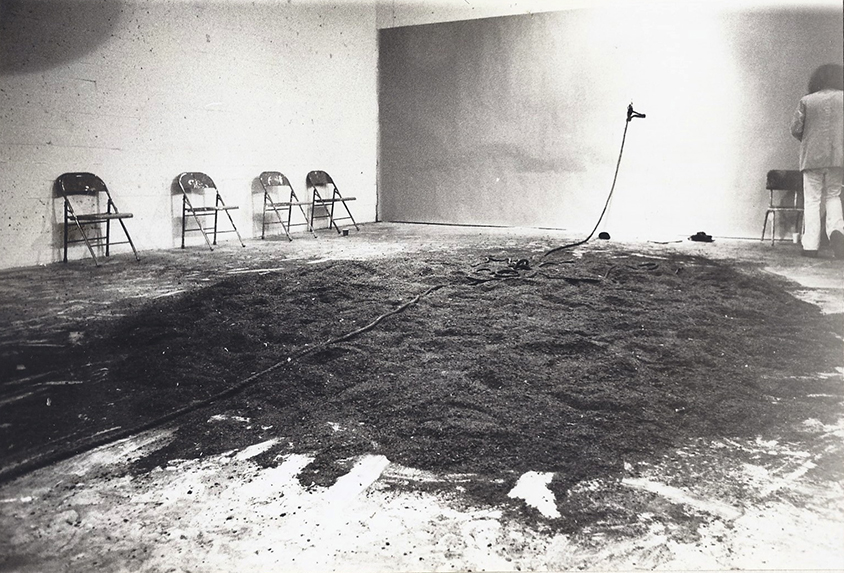

Darryl Sapien, Diffusion Capsule (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Diffusion Capsule (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Then Diffusion Capsule was a structure divided into two rooms that I built in the Diego Rivera Gallery, and I lived in it for a week, which kind of goes back to Tom Marioni living in a gallery. I had been reading Jack Burnham's work and was interested in his divisions between nature and culture and physical and intellectual. So I made one room light, for all intellectual activities, and one room dark, for all physical activities. The dark room was covered on the floor with hay. In the light room the floor was all filled with debris - hard junk, broken chairs and tables. I remember there was a broken mannequin in there and wire and tyres and stuff you would see in a junkyard. There was a tube connecting the two rooms. If I wanted to read, I'd have to wiggle through this tight cardboard tube through the dividing wall into the light room. Then for eating, sleeping or other physical activities I would have to wiggle back into the dark room. It was like a B. F. Skinner experiment. I went a little bit stir crazy in there and decided I was going to have a revolution and break the rules. I started knocking holes in the walls in the dark room (laughs). In the end, though, I dropped the entire side wall on one side, so you could see a cross-section of the dark room and the light room. That's what the show was when I had the opening, just exposing the living quarters.

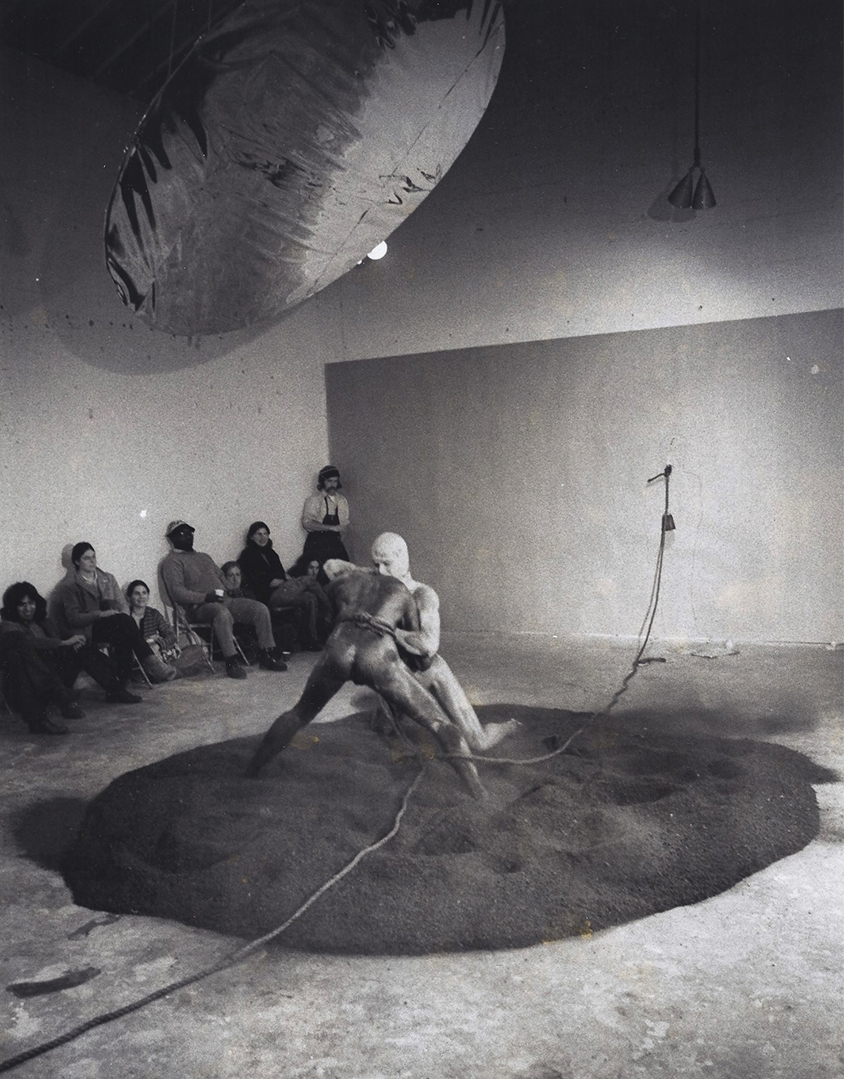

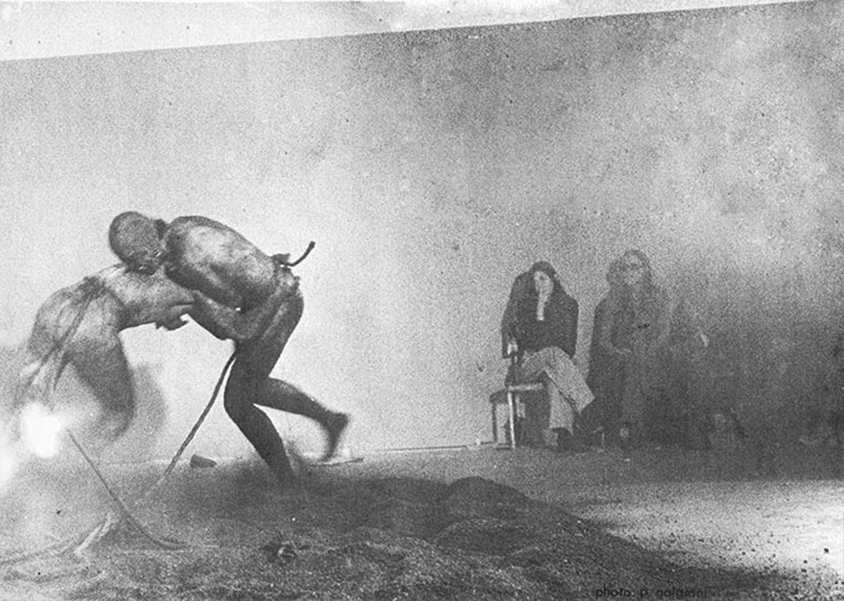

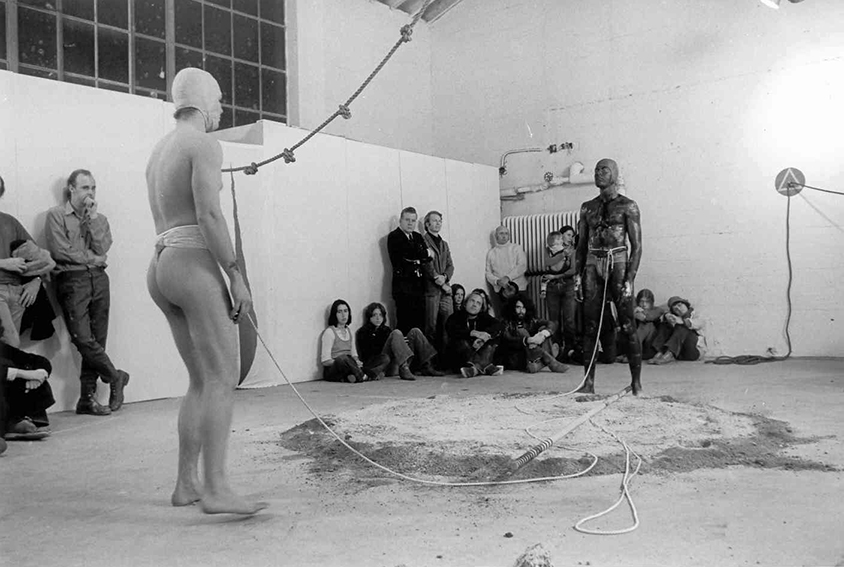

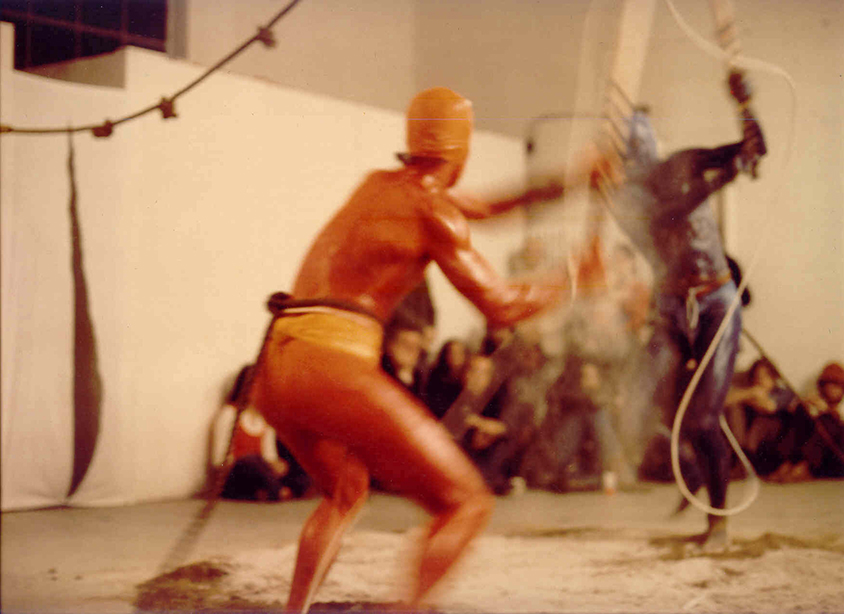

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

So this was very early but before that the one that really put me on the map was Synthetic Ritual (1971). This was the first one I did with Mike Hinton - where we wrestled in a circle of what was supposed to be dirt, but ended up being something else. At the garden supply they were sold out of topsoil, so we had to buy sacks of steer manure, fertiliser instead, which added the dimension of smell - a very powerful smell at that. That idea was the one I had immediately during that summer when I was reading Avalanche magazine – just finding out as much as I could about artists' performances and thinking this is really meant for me; for my physicality, my athleticism. A lot of my performances were pretty athletic: they required physical exertion and daring.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Why the title Synthetic Ritual?

Because it was intended to be a ritual; a ritual about conflict resolution and the unification of oppositions. Hence we had orange and blue walls on opposite sides of the room, which are opposite colours on the spectrum. Then the orange man and blue man each emerge from their respective walls and meet in the middle. The idea was that we would start out passively and then it would escalate slowly to a contest of strength and become a full-out wrestling match, where we both try to displace the other from the circle in the center of the room. Our meeting begins with a very passive kind of tactile exploration while blindfolded.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

At one point we take off each other's blindfolds - and once we can see each other it turns into more a test of strength and who can control this little patch of dirt: it's just a territory. But the whole time we were attached by ropes to our respective walls and so through the process of the wrestling our opposite colours were sort of smeared off on each other, so we both became a kind of a neutral, tertiary colour. Then we were throwing each other around in such a way that we were tangling ourselves up in the rope. We were kind of knotting ourselves together and losing our opposite colour, which was symbolic of reaching a state of equilibrium - and we would also reach a state of equilibrium in exhaustion.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

And the perfect circle we had begun with became a record of our conflict, because it was all splattered and sprayed around the room. I wanted to involve all the cardinal points of the room in the performance. First the two walls, the orange and blue at oppose ends, and then the floor with the circle of dirt. Then above it I had stretched Mylar over a big disc that was hung from the ceiling, so that you could look up and you could see a reflected image of the two wrestlers. That's always been another hallmark of my performance - that I want to involve as much of the space as I can, all the dimensions, the full spatial potential of the room or the building or the landscape.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Synthetic Ritual (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Then it was synthetic because it wasn't really a ritual. Rituals grow out of long traditions of cultural generations and repetition over time to gain their significance. I just made up a ritual that I thought would be what a good conflict resolution ritual might look like. And like all art, it's a reflection of its time. The hippies were kind of over, but there was still a lot of that 'back to the land' mentality: back to the ways of our ancestors, back to shamanism, back to ritual. It occurred to me that all of our rituals are kind of lost. For most of us you just have to find your own way. So this was designed to be a hypothetical ritual of conflict resolution. It was a reflection of internal states, too, of just my own thinking, my intellectual side struggling with my instinctive side, my emotional side struggling with my rational side - and the warm and the cool, the hot and the cold, the dark and the light. So it was illustrative of my own mentality.

Terry Fox also used explicitly metaphysical allusions in his work.

I was interested in him because he was taking out what was inside of him and putting it outside, and what was outside he was putting inside. I was interested in his fascination with the labyrinth of Chartres [for example: Terry Fox, Yield (1973), University Art Museum, Berkeley]. And I knew he had a lot of medical problems. I just saw it like he was taking his intestines out and spreading them on the floor - in a labyrinthine form. Then I met him and he was a pretty interesting guy. For me, Bruce Nauman also - I liked his static work just as much his performance. For example, the folded arms with the ropes coming out of them [Bruce Nauman, Henry Moore bound to fail, back view (1967-70)] and some of the things he did with casting and wordplay to me were really enlightening.

How did you prepare for Synthetic Ritual?

We didn't rehearse it! (laughs), I just had to get the room booked. It was the same room in which I did In Transit - the famous Studio 8 at the Art Institute. I just planned it out. We had to do it during Christmas break so the room was freezing cold, you can't prepare for that.

Did the performances usually occur once only?

Yes. The only one that I did more than once, I believe, was Hero (1980), which I originated for the Newport Harbour Museum at Newport Beach in Orange County, California. I did that twice down there. Then I came back and six months later I rented the Victoria Theatre in San Francisco - the cheapest one you can rent in the Mission District - in February, again it was freezing cold and no heat. I wanted to see if I could sell tickets and maybe make some money and possibly break even for the first time ever on a performance - which was not the case, not by a long shot. So we did maybe ten performances. Then Pixellage (1983-4), which, although I didn't perform in it, I consider one of my performance pieces - I created it with my choreographer collaborator Betsy Erickson: that was repeated 16 times at the Opera House, San Francisco. That was a big hit for me - I was very proud of it and still am. But I wasn't in it. (laughter).

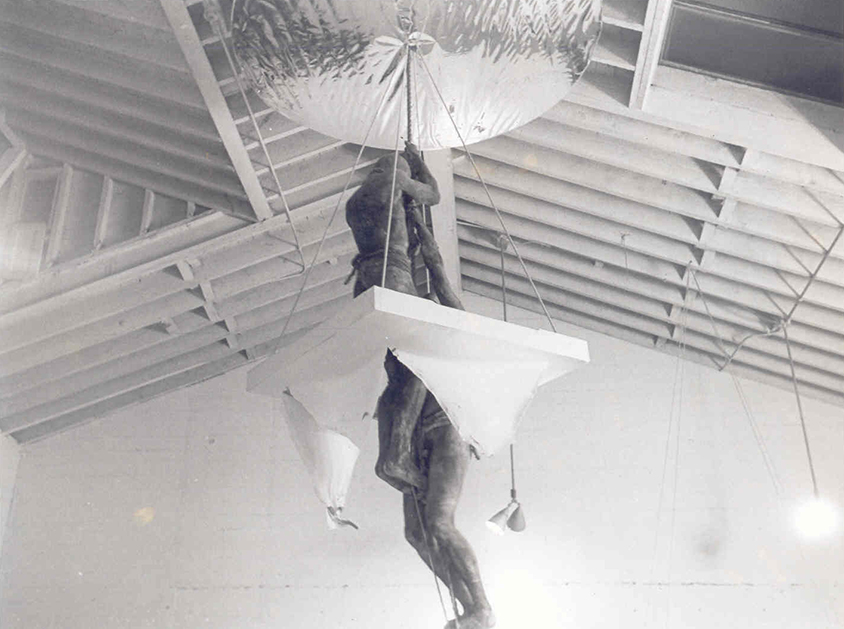

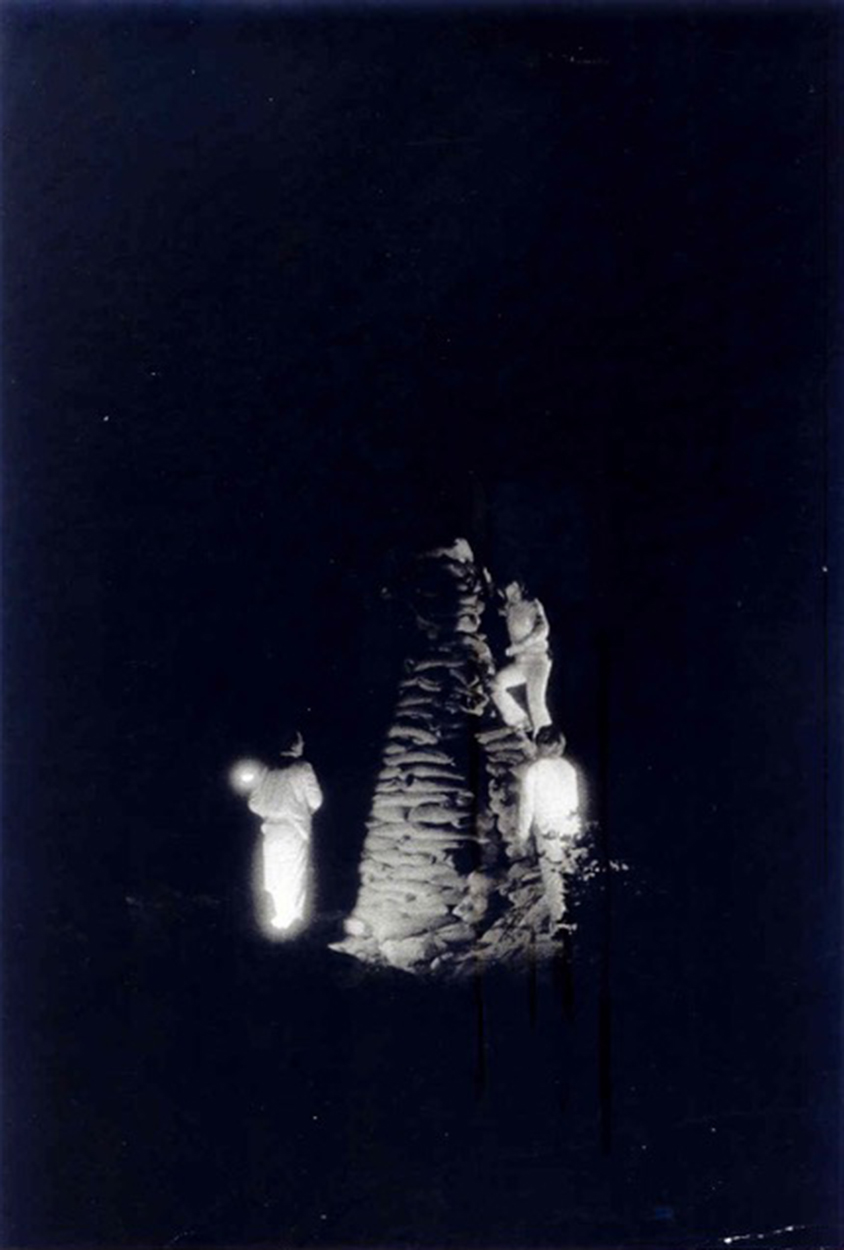

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

One of aspect of shamanism is the unification of opposites.

Well yes, they connect opposites, they're there to connect opposites: to connect the earthly world with the spiritual world and the human world with the gods. They are mediums and are able to transit between the spiritual and physical world. I did a performance called Initiation (1972) that was all about shamanism. I had read Mircea Eliade's Shamanism [Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, 1951], and that influenced that performance. And that was, again, done in Studio 8 at the Art Institute following almost a year exactly after Synthetic Ritual, with Mike again, and also Conny Vokietaitis, who was what you could call the hierophant or the Master or Mistress.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

She was costumed as an ornithopomorphic figure, bird-like, which in shamanic interpretation means she's able to transit between two worlds - the sky/the heavens and earth. In a great many shamanic traditions the shaman can fly or levitate or has a spirit animal that's a bird that takes messages back and forth from heaven to earth. And it was also part of the unification of opposites theme. In the beginning I had to undergo a kind of a ritual sacrifice, because to become an initiate you give up your old self.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

But Initiation was very much about comparing the role of the artist to a kind of modern day shaman who's capable of transitioning between two worlds - maybe the art world, the world of make-believe and the real world, or the spiritual world and the physical world. So we bring back information from out there for the rest of us to look at. But the first thing you have to do to become a shaman is you undergo kind of a ritual death - or you sacrifice yourself. So that's how Initiation started, with Conny performing the ritual sacrifice. It was all based on the idea of connecting the artist's position in contemporary society with a shaman's in a more traditional society.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Initiation (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

One of the things that seems distinctive about your work is the use of narrative.

Initiation was my first real narrative piece, where there was sort of an episodic sequence of events that all had their own significance as part of a larger story. Whereas other ones were task oriented. In retrospect, it seems like every time I fell into a narrative I got myself in trouble. Sometimes I think I do better when I do one action stretched out over a period of time - or I have simultaneous things going on at the same time.

Portrait of the Artist x 3 (1979) was simultaneous, wasn't it?

Yes. Portrait of the Artist x 3 came to mind after I moved here to the Outer Richmond district near the beach.. There used to be an amusement park that had been long closed down called Playland at the Beach. In 1979 it was just a barren expanse of sand dunes with the ruins of the roller coaster and the diving bell and so forth jutting out of the sand like some lost civilisation. Apart from that, it was abandoned and desolate. So I made a hole in the fence and went in there and decided this looks like a good place for me to do something - this has got Darryl Sapien written all over it (laughs). The idea behind that was that, like all amusement parks, you just walk from one amusement to the next: the show doesn't come to you, you go to it. That worked out very well because the audience was free to go or be wherever they wanted. And all three of the events, although linked, weren't necessarily in order. There was an order to them - because each of the three events that were going on simultaneously represented one aspect of the artist's life cycle - but you didn't necessarily have to see them in order to make sense of them.

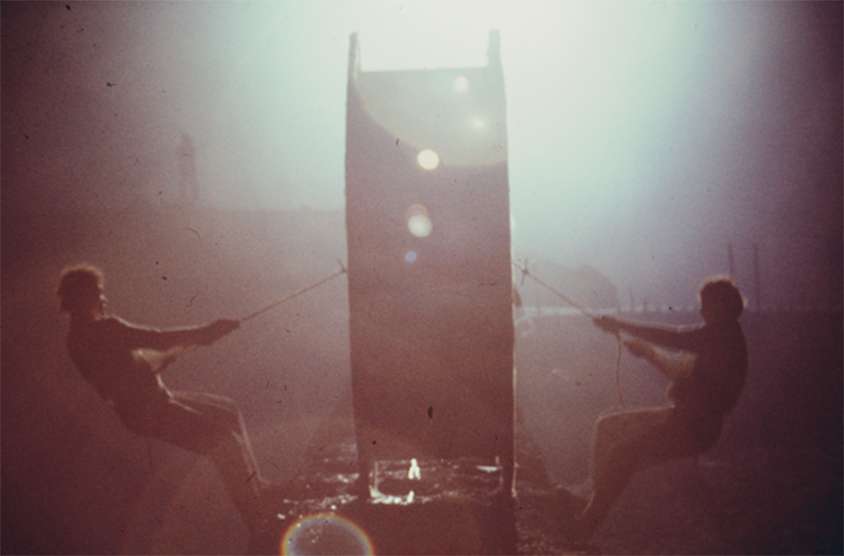

Darryl Sapien, Portrait of the Artist x 3 (1979). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Portrait of the Artist x 3 (1979). Courtesy of the artist.

So that was, again, quite personal?

It was my take on what it's like to be an artist. The beginning part is just getting a grasp on how to represent the world around you, which was represented by two performers with blowtorches copying geometric shapes that were projected against a concrete abutment; a circular, concrete abutment that was coated with waterproofing tar. They went at it with a blowtorch - it was like drawing. They were just trying to grasp basic form by copying the projected images. The next stage is the hard work aspect: the toil chapter of a career, just plain hard work and the perspiration of it. Here the performers were building a tower out of sandbags. I wanted to use all indigenous materials, materials that I didn't have to import. There was sand all around so filling sandbags and stacking them up and making a tower seemed to make sense in that regard.

Darryl Sapien, Portrait of the Artist x 3 (1979). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Portrait of the Artist x 3 (1979). Courtesy of the artist.

Then the final site was inside what was formerly the diving bell. A round concrete wall, about thirty feet in diameter and 12 feet tall, with no door, circumscribed this area. The only way you could get in or out was with a ladder. This stage was meant to represent kind of the endgame of the artist's career. The whole thing was filled with debris from the demolition of the park. It was a real matrix of detritus of civilisation and kind of otherworldly. But in the centre there was a round pocket - another circle, a cylindrical void in the floor, - which I imagine is where the diving bell would just sit when it reached the bottom. Originally, when you went into the diving bell you are supposed to think you're going into the ocean, but it's just a big aquarium. So the diving bell would go down and sit in this pocket while you look at the fish. Anyway, we cleaned out the pocket so it would form a perfect circle in the middle of the debris field. Then we put a table and a chair in there and one of the performers was sitting in the chair, knee-deep in crumpled-up papers, typing furiously, ripping out paper, crumpling it up, throwing it, rip it up, type, rip out, crumple, throw - until he was burying himself in his own work. I was the other performer and, while he was doing that I was running around trying to make something out of all the debris - trying to make a makeshift ladder or some way to climb out of there. So he was busy burying himself in his own work, while I'm busy building a means of escape. Personally speaking, it's like what's going on in my brain when I'm at an impasse with my work: I'm trying to come up with an idea, rejecting the idea, throwing it away, trying a new one, rejecting it, throwing it away, until I'm like up to my neck in rejected ideas (laughs). Meanwhile, one part of me just wants to break out, wants to get out of that impasse, get out into a fresh horizon so that fresh ideas could come. Finally I did build a way to get out. The performances at the two other locations had ended earlier. So everybody was now standing around the edge of the diving bell, watching me, and finally I did build a means of escape, and then just jumped - jumped for it. And I didn't tell anybody I was going to jump. I surprised everybody. I just wanted to disappear into the night like a fugitive, like a jailbreak.

Darryl Sapien, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

You did a series of performances linked to specific sites, including Crime on the Streets (1978) in Adler Alley in North Beach - and A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art (1977) that required an action in Jessie Alley, South of Market. Were there specific things you were trying to engage with in those sites?

Some more than others. For example, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974) was very much in a site – the ruins of Sutro Baths - that spoke to me. I didn't know what I wanted to do, but I knew I had to do something there. The breakthrough for Split-Man Bisects the Pacific came when I saw a Hare Krishna parade going through Golden Gate Park. The devotees were hauling an enormous wagon with their Guru on it. He was sitting in the lotus position on top of what looked like a multi-story Hindu altar - all feathered and colourful and people dancing around it. There was a team of his minions hauling this wagon by manpower, all dressed in their costumes. The wheels on it were so big they fascinated me. Then I put that together with the wall at Sutro Baths and thought: what if I just took one wheel and made it into kind of a unicycle, and then I combined that with a Vitruvian man. So the wheel then became a symbol for man, but it was a split man again - Mike [Hinton] and I on opposite sides, pulling against each other through a rope passing through the centre of the wheel.

Darryl Sapien, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

We couldn't see one another, but we had a task that we had to accomplish together. So we literally harnessed the energy of opposites in that we were both leaning away from each other so that the opposition of our body weight would balance the wheel. The rope that was wrapped around our waists was like an umbilical cord that passed through the centre of the wheel and connected us to one another. Both our lives both depended on the tension produced by our leaning back, leaning our weight back, cantilevering ourselves over the ocean, and using each other's sure-footedness and balance to coordinate our movements.

Darryl Sapien, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Split-Man Bisects the Pacific (1974). Courtesy of the artist.

The sound was the call and response that we were doing: it was a code we used to coordinate the movements of the wheel; microphones in the wheel broadcast our voices to the top of the cliff amongst the spectators. Our movements had to be precise otherwise we'd roll off the wall into the ocean, so we were steering it by pushing it with our feet. The idea was to get from the shore to the island and back: the classic Jungian night sea journey, going into the dark sea of the unconscious at night and coming back. That's why our faces were half-white: one side of mine was white and one side of Mike's was white. If you superimposed our faces it would have become a whole face or a whole circle - reflected also by the wheel, the white wheel that we were rolling towards the island at night, with a big searchlight on the cliff behind, tracking our progress. So that site generated that idea.

Darryl Sapien, A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art (1977). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art (1977). Courtesy of the artist.

What were the origins A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art? How did that evolve?

To me a bridge is always a way of uniting opposites: opposite sides of a river, opposite sides of a canyon. And I thought, well, if an artist's job is to unify opposites, why don't I just make my own body into a bridge? The only way I could do it would be through a photomontage. I had to find an alley to do it in where I could attach the ropes and get away with it without getting arrested. So it was Jessie Alley above Breen's. Tom Marioni's Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA) was one end of it. Tom didn't want me to do it, but I did it anyway.

Darryl Sapien, A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art (1977). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, A Bridge Can Also Be A Work Of Art (1977). Courtesy of the artist.

He was mad at me (laughs). Because I had violated one of his rules when I did Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975) at MOCA, where I painted a section of wall inside that dark and grimy interior white, because I wanted it to look like a slice of white light. And Tom had said you can't do anything that can't be undone. But I had this idea, and there was just no way I could have done it otherwise. So I went ahead and did it. And then he hired David Ireland to return it back to its original state. [Tom Marioni with David Ireland, The Restoration of a Portion of the Back Wall, Ceiling, and Floor of the Main Gallery of the Museum of Conceptual Art (1976)]. So it was Ireland erasing Sapien.

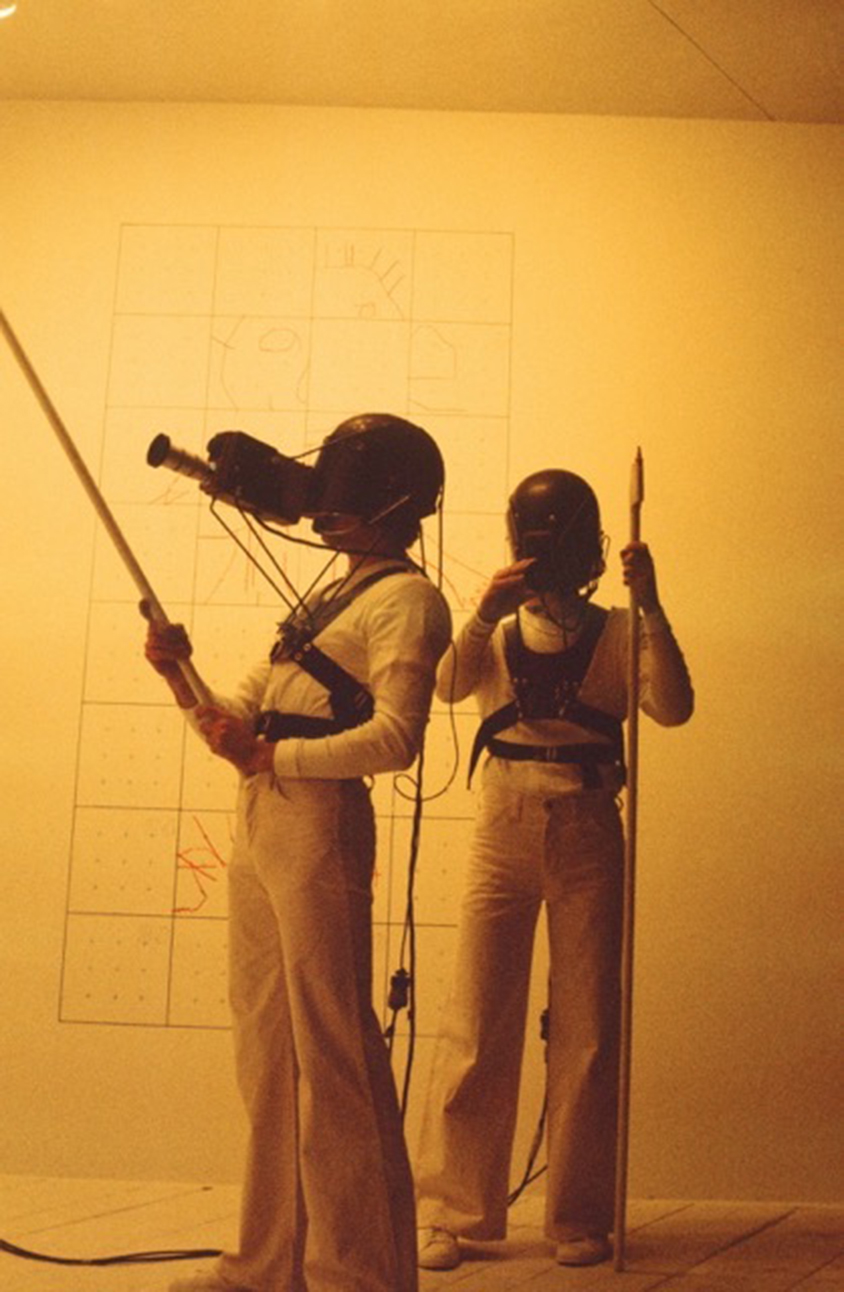

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Tom suggested I ask you about the marking of the back wall.

It was to create the space to do it in. I wanted something that would be carved out of that space. I wanted something that would look like it was a wedge of pure light. I didn't see any other way around it. I had built two sidewalls out of drywall, but I had to paint the back wall, the floor, and the ceiling. I believe I painted the ceiling, maybe I didn't. So when the sidewalls were taken down what remained was kind of a V-shape on the wall and then another V-shape on the floor and ceiling. Which I thought looked pretty cool, kind of like an hourglass, you know. But Tom wanted it to be the way it was.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

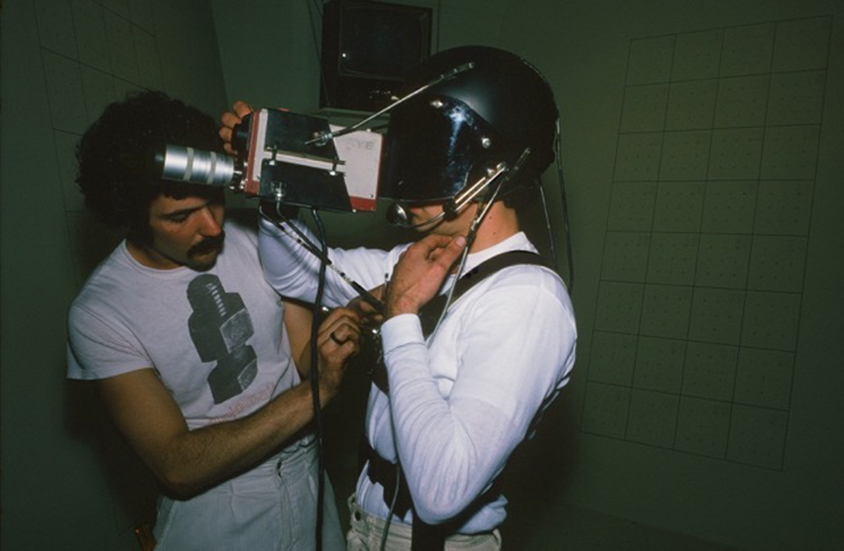

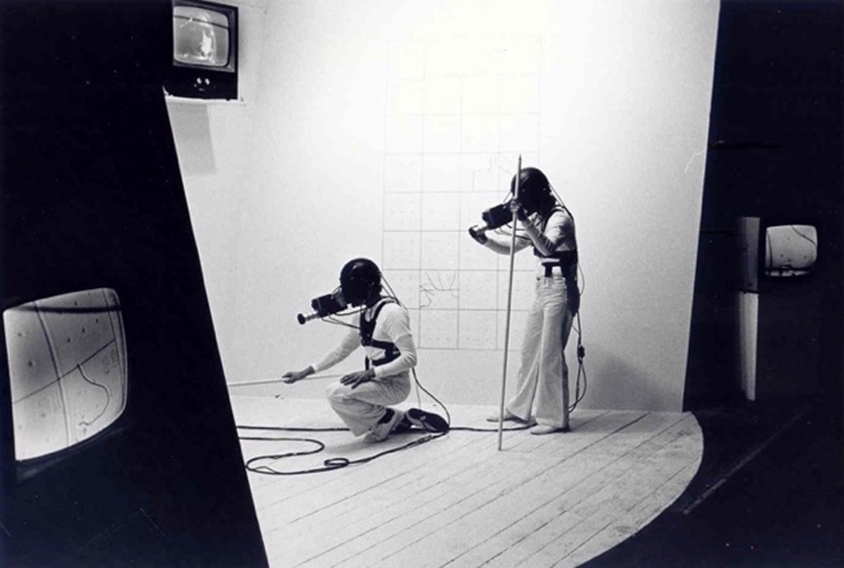

Tricycle took place over two floors. A woman, Cyd Gibson, who was directing Mike and I was situated on the floor directly above us and could only see the floor below through our eyes, which were the video cameras that we wore on helmets, mounted in front of our face. She was trying to direct us to reproduce square-by-square two drawings by giving us verbal instructions using a code based on the clock and compass. She tracked our progress by looking at two video monitors that were reproducing what Mike and I were seeing in real time. So without the video working there would be no performance at all. But the audience could also participate in that, because via other video monitors they could conceptually be inside of our helmets and see the performance as we were seeing it in real time. In this piece my only interest in using the video was to give the audience a different way of seeing the performance. It was also a way of documenting it, but fully integrated. It would put you inside the artist's head. The drawings turned out to be copies of children's drawings I'd found on the street, one of a boy and one of a girl, so it was kind of a techno-creation ritual.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Do you think the technology is depersonalising? Or extends or emphasizes the task-based nature of the performance?

I like to refer to those video-costumes as more mechano-morphosizing or making a sort of android: a weird marriage of human and technology, as if the cameras were grafted onto us and they were actually part of our living body. We were seeing through artificial eyes and it was a marriage of our anthropology and our technology together as if it were semi-robotic. And especially in Tricycle, in which we were under the control of a disembodied female head and following her instructions through a code, and I liked that it referenced the concept of the artist and his muse. Also I liked the way it looked (laughs). I thought it was edgy-looking and no one else was doing anything like that. I wanted the video to be a functionally integrated aspect of the performance. In Tricycle we used a code based on the clock and the compass. In lieu of dialogue, I wanted something that would be more encoded into the performance in the same way, as the performance itself was an extended task.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Tricycle: Contemporary Recreation (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Did you think of the white wall and floor as still integral to your work after the performance had finished?

No, the performance was over. So paint over it if you want to. On the other hand I haven't been invited to any of Tom's beer parties.

Since 1976?

(laughs) Yeah. I still like him. I don't think we have a feud going on over that. And David Ireland was my friend for a long time.

Was MOCA important to you before that point?

Yes. I'd gone there to see the exhibition All Night Sculptures (1973). I was really impressed with John Woodall's piece [John Woodall, Marking the Dilemma (1973)] - and many of the other ones that I can't recall. I remember thinking this is a good show. Then when I was invited to be part of the Second Generation (1975) show, I knew I had to do something really good because I wanted to make an impression on other artists the way I was impressed by what I had seen there before. I had heard of MOCA even before that. I remember I went there with Mike Hinton and Kathy Bigelow – who then became a film director, of course. She said there's this guy, Tom Maroni (sic) and he's got this place called the Museum of Conceptual Art; do you want to help me find it? So we all hopped in Mike's VW Bug and drove down there from the Art Institute. We finally found it, but we couldn't get in, they were closed - it was just a little, dirty door on 3rd Street with a long stairway to get up.

Were you involved in the Breen's Bar gatherings?

I did go there one time when John Cage was there. I had some beers with John Cage and with Tom. I think that was after I did the performance. And that was fun. But then when Breen's closed I never did go to Jerry and Johnny's, to where Tom relocated his beer-drinking art form. Breen's was a good bar. It used to be a big press bar: newspaper guys would go there, because the Examiner and Chronicle buildings were nearby.

When I did that bridge in Jessie Alley, I was going to go to the Bologna Art Fair with Lynn Hershman, who had organised this thing called The Global Space Invasion. I was part of it and she was taking us all to Italy. I thought, wow, that's great, I've never been to Europe before, what am I going to do? So I thought, well, I'll do a bridge there, too - a human bridge - then when I get back I'll take the pictures from Italy and from San Francisco and I'll weave them together so that one end of my body is in Italy and the other is in San Francisco - I will use my own body as a bridge between the two locations.

Was there an audience to the performance element in Jessie Alley?

No. I did it very early in the morning, because like a lot of the things I did I didn't ask permission. And if I did, they would say no. I didn't ask permission to do Split-Man Bisects the Pacific. However I did get permission to do Crime in the Streets.

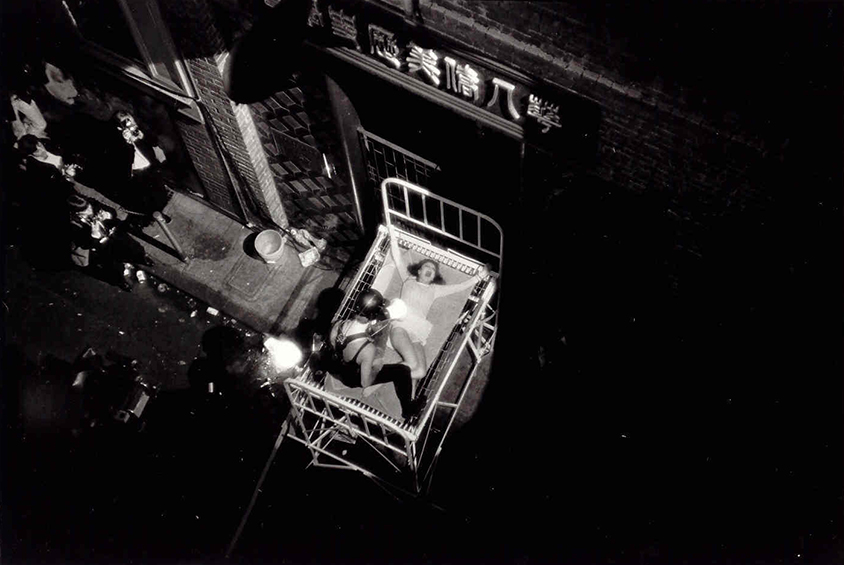

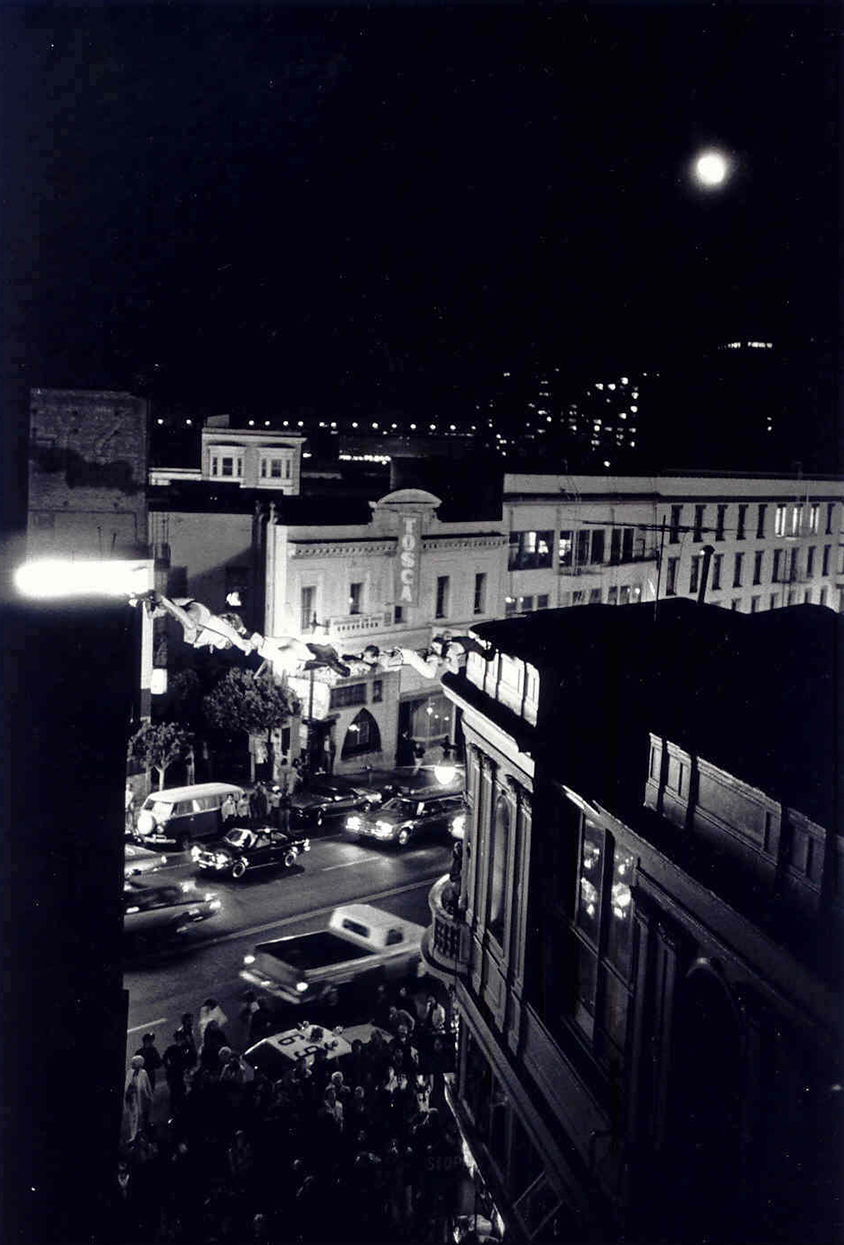

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Yes, because Crime in the Streets was quite a large-scale public event.

For Crime in the Streets, I knew I needed to find an alley that was narrow enough for me to make a human suspension bridge with four or six people - preferably four, because six might get too heavy. To get a permit to block the street I had to go before the Police Traffic and Safety Committee at City Hall and explain why. As fate would have it, all those committees were chaired by one member of the Board of Supervisors, and in this instance the chairman was Dan White, who about 4 months later assassinated the mayor of San Francisco, George Moscone, and supervisor Harvey Milk. I got my permission to do Crime in the Streets from Dan White himself, who was very concerned at the time as to whether my performance would frighten people - will there be violence? Will there be guns? I said, well, there's a track-starting gun: it's not real; there won't be anything to scare people. It's just theatre. So he gave me my permit to do Crime in the Streets - which I find to be ironic to this day.

Interesting that you call it theatre – most artists at the time would not have used that term.

I didn't know what else to call it, and I had to kind of soft pedal it to this committee. They would understand theatre, but performance art might be the kiss of death for me to get the permit I needed. I had to be somewhat accommodating to what they already knew, so I didn't go into detail too much - oh, it's just street theatre.

Crime in the Streets is perhaps closer to theatre than some of your other performances.

Yes, I would say so.

Did you author it?

Yes.

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

So there was a scripted text?

It was a text, but it was based on events that had happened to members of the cast, including myself. For example the reason there was a rape in the performance was because my sister had been raped that year or the year before, and I wanted to create a situation where I could punish the rapist. And also, metaphorically speaking, I was living in South of Market and there was so much noise: there was a big loud machine next door that they would run for days and days and all weekend long. It was a big, industrial machine. I couldn't sleep. I couldn't concentrate. I felt like I was being violated. I felt like my brain was being raped by this sound. So that comes through in the performance as rape by noise. There is a lot of pounding – pile drivers in the background - and the city is a machine that consumes its weakest members to keep its fires burning. So this was all about weak members of society being exploited and used up and ground up and burnt up as fuel to fire the engine that keeps the city moving and keeps it working.

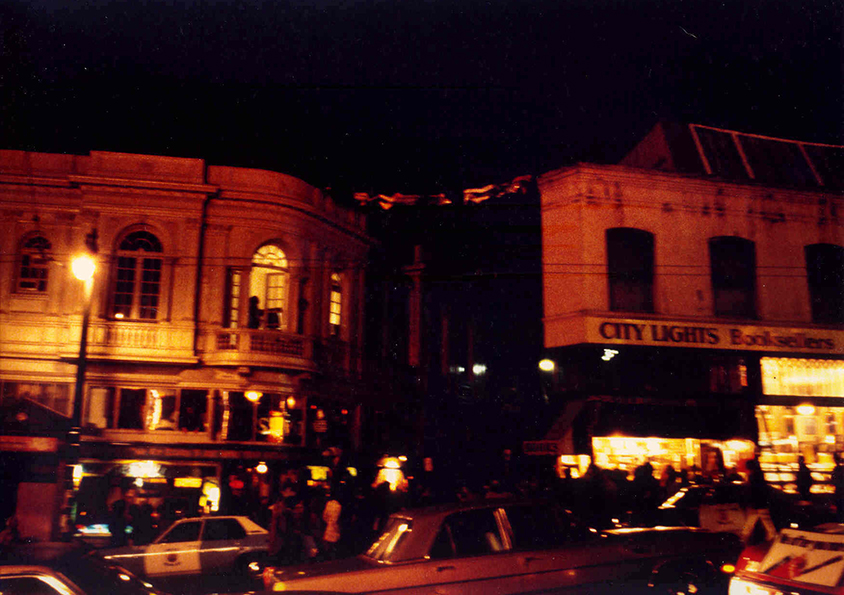

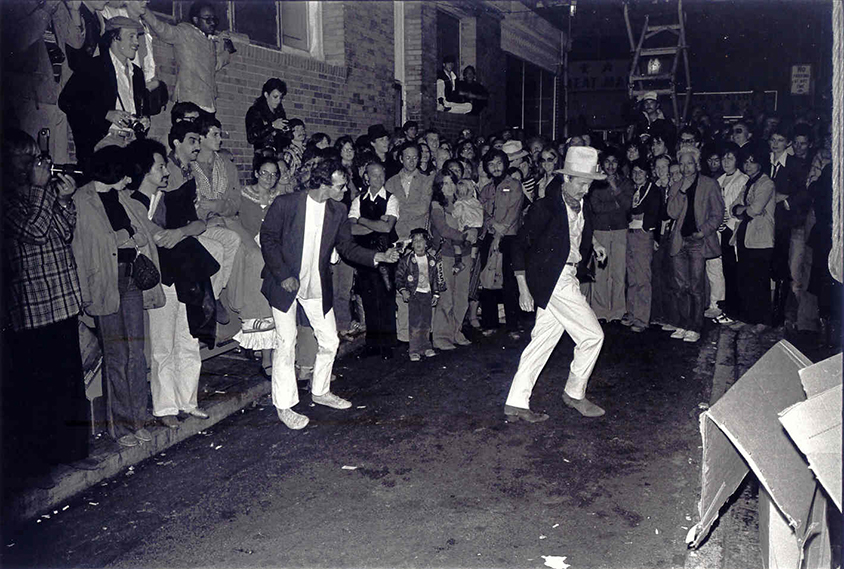

Was it confined to Adler Alley?

Yes. It's between Vesuvio's [bar] and City Lights [bookshop], so that was a good location, although neither one of those establishments had any idea what was going on. I ended up getting my electricity from City Lights, because I knew one of their cashiers. But they weren't banking on all the power I was going to be sucking out of the place (laughs) and we blacked them out. And [Lawrence] Ferlinghetti came running out, saying who the hell is blacking out my bookstore? (laughter). I just was up on my tower hoping he didn't see me. There was so much chaos - I mean it was probably the most chaotic performance. Yeah. The punk rock contingent was there - the Mabuhay Gardens was just down the street. And between all the heckling and everything going wrong, I thought it was a dismal failure. It was out of control really: it was like a riot. But I look at the tape now and I think, well, I bet no-one's ever tried to do anything like that since then and probably never will.

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

It comes across as a performance with a really intense energy.

Well, that fouled it up at the time for me, because we had rehearsed it quite a bit - there was a lot of flying trapeze, a lot of heights involved. So we had to know what we were doing, we had to rehearse it. I had a Minotaur to come out the manhole cover, out of the sewer, so I had to make a dummy manhole cover that would be light enough for him to pick up but still strong enough for people to stand on. And then he was supposed to have a smoke bomb go off before he came out. But the smoke bomb blew up and he came out of that manhole cover like a Minute Man missile, because he thought his costume was going to catch fire. And then he had to take the rape victim back down into the sewer. Anyway, we rehearsed it at a warehouse on Brannan Street that sort of reproduced the plan of the alley - long and narrow, with high sides, sort of like a basilica type of a warehouse. But it was empty. And I thought, because I had this permit from the city, that the police would show up and put up barricades and block people off. They didn't do any of that, they just stood around, smoking cigarettes and waited for somebody to get hurt or something, I don't know. But I said aren't you guys going to keep people out of here? No that's not our job, that's your job, buddy. I said, well, where are the barricades? Well, we don't have any (laughs). All right, so consequently the alley just got filled with people. So there was really no room to do anything we planned. But we ended up just making little clearings where we had to, and people would clear out when the firecrackers went off, or they'd clear out when there was a lynching of the scapegoat and they were throwing baseball bats - poor Mike, who was taking his lumps in that situation - or when the Minotaur came out of the manhole cover or when the firecrackers went off, people would back off far enough to not get singed (laughs).

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Crime in the Streets (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Do you want the audience to feel that element of risk?

Risk-taking has been part of a lot of what I've done. I think it goes back to my background in athletics, and also being a carpenter and working on tall buildings and overcoming a fear of heights at a very early age. And walking up on narrow ledges, carrying tools and lumber and learning to ignore that you're high up or that you could fall. I mean, it's in the back of your mind, of course, but if you worry about it too much you will fall. I started doing that when I was 16. So in a way it heightens the audience's attention.

Darryl Sapien, Splitting the Axis (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Splitting the Axis (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

In a number of the performances technology seems to have had an important part in its own right – I'm thinking of Tricycle, for example. At the end of the video documentation the camera spends time showing the helmet, objects and the cameras you used. Some of your drawings or paintings are of the technology or equipment used in the performances. Splitting the Axis (1975), while very obviously focused on the physicality of splitting the wood, distributed the images of the action around the Berkeley Art Museum space on monitors dispersed at all levels. Technology seems to play a very important part in how you articulated these performances.

I was interested in how technology could serve a purpose within the performance. You mentioned Splitting the Axis. Like Synthetic Ritual it was a reflection of its time. It was still the late hippie era and it was getting back to the land, getting back to the ways of our ancestors. So the pole itself represented the world tree in Native American shamanic tradition: the tree that connects the sky with the earth and the heavens with man, and we were destroying that, and we're destroying it because we'd lost our way.

Darryl Sapien, Splitting the Axis (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Splitting the Axis (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

It can be seen as cutting down forests or polluting the ocean. It was a metaphor for just how we're undermining these traditional ways of life that had maintained and supported us as a species for all these millennia. Then with advances in technology and increasing population it's accelerating. But, on the other hand, I wanted to show how our technology, too, was doing the same thing to us. I wanted to have the technology of the sound and the video fragmenting the performers and sending bits of a foot over here, or the sound of a mallet pounding wood over to the bookstore, or just a fist with a hammer in it - disembodied at the opposite side of the museum.

Darryl Sapien, Splitting the Axis (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Darryl Sapien, Splitting the Axis (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

And also it would afford a way of the audience seeing the other side of the performance: looking at it from one direction with the naked eye, but maybe seeing it on a video monitor from the opposite side. So just in a kind of a cubist way giving multiple points of view of the performance and exploding it to various points around the perimeter of the museum. And those points were plotted in conformance with a diagram of the main action of the performance - which was two wedges penetrating a circle. I superimposed this diagram over the Museum floor plan, and then superimposed the path of travel over that. Where these intersected I would place a monitor or a speaker that would have a fragmented aspect of the performance displaced far from its source - that people moving around the gallery would walk into unsuspectingly. It was like some aspects of the performance were cut out and then relocated. Meanwhile, we were so busy with our act of trying to split this tree in half that we weren't aware that what we were doing was actually accelerating our own disintegration as well. We are so focused on harvesting the resources of the planet that we're not aware that we're cutting our own life short, or we're actually destroying ourselves in the process.