Tony Labat

Interviewed by Nick Kaye, San Francisco 20 May 2016.

Follow the links for discussions of: First Lesson (1975) | Solo Flight (1977) | Kidnap Attempt (1978) | The Gong Show (1978) | Terminal Gym (1980-81) | Fight (1981) | Peace Sign (1987)

From very early on in your work you were making performances of one kind or another. Why performance?

I can't think of many things I have calculated or planned. It's a really interesting question, particularly to look back. I could start by being in college - in the art department in Miami Dade Junior College - and being very green; not very well informed about what was going on.

But Les Levine was in residence on campus. And one thing that I responded to or I was attracted to was - it looked a little suspicious, as if it was a persona. I remember that most of the time he was wearing these tacky, horrible, Hawaiian shirts, and was barefoot. This was about 1974. There was a suspicion in me that there was something being played here: there was some sort of projection, there was some sort of irony about the Hawaiian shirt and Florida and being barefooted. Maybe I'm looking at an artist playing a part, projecting a part, projecting a persona. And in those days the media/television department was separate from the art department, and he ignored the art department and wanted to be in the television studio. So that immediately did something, provoked something in me. Then there was the video, which he's sitting on a chair, ranting about talent: how if an artist wanted to sing, an artist should just sing; if an artist wanted to dance, just dance. And I remember him throwing some coloured pigments on the floor. The camera angles kept switching. He was dancing and singing and continuing this talk about craft and talent, which, looking back on it, were really issues of conceptual art in relation to performance. At the same time, I found it incredibly entertaining. So to answer your question, I can see a seed being planted during that experience.

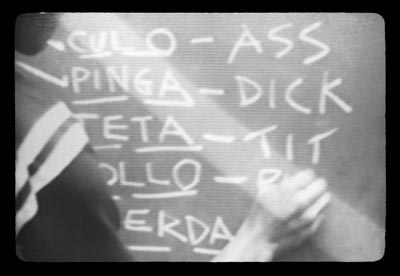

Tony Labat, First Lesson (1975). Courtesy of the artist.

Also, I was lucky to have the artist Robert Thiele there as a professor. I think he started noticing me and my interest and how 'lost' I was - a Cuban refugee knowing very little about art, but having this interest. It started, too, with me challenging Robert. For one of the first assignments I brought baggies with my dog's shit in it. I'd made this horrible mirror box with all the dog's shit hanging in it [First Lesson (1975)]. What really got to me was how seriously he took that piece. There's a word with Cubans: joder, which is to fuck with things - to challenge things with a mischievous kind of humour. What if I bring dog shit? What's going to happen? To make a long story short he started bringing films and videos from New York, from the west coast. I think he perceived me as being serious. There was something about the stuff he brought to class, the films and videos and documentation of performances that just really got me. It was love at first sight.

Tony Labat, First Lesson (1975) (detail). Courtesy of the artist.

And I remember buying an issue of OUI magazine - the girly magazine - and it had a whole spread on Chris Burden. Of course, it was all about like the Evel Knievel of the art world: like he was the butt of the joke - look at this crazy guy and what he's doing. It just turned me on so much, the possibilities of what art could be. There was a bit of the entertainer in me: entertaining something, entertaining an idea; of doing something live that would entertain ideas. That really got to me. It was Robert Thiele that told me about Howard Fried. They had been together at the Whitney Biennial, around '74. He told me about Howard and the San Francisco Art Institute where Howard was teaching and how he had just acquired 2 Porta-Packs for the Sculpture Department. And he point blank told me: Tony, get the hell out of here. Go there. It was also a moment when the Cuban refugee exile community was really suffocating. So I went west.

So that feeling of being lost was important to your early work?

Yes. The exile community was filled with censorship. Being Cuban was really connected with exile. The atmosphere was very suffocating. My foundation was with the Cuban revolution. I was very idealistic. Coming from Cuba in 1966, I felt comfortable with the hippies. When I would meet hippies and I would say that I was Cuban, they would connect me with the revolution. That was my true exile. It was very welcoming. In that context things could be questioned, things could be talked about. And I realized that the role of the artist was to question things, not to have answers. At that time to question anything, particularly politically, within the Cuban exile community was a no-no - you didn't go there.

I hadn't really understood that the sense of displacement in your early work reflected a displacement from the community here rather than necessarily from Cuba itself.

Absolutely. Yes, absolutely.

Les Levine's work is politically charged, but also equivocal about its own politics.

That's true, that's true.

Whereas your work to me seems more politically raw. It confronts you directly with questions of place, identity and political process and of cultural fitting/not fitting in a way that is unresolved and upfront - unlike most of the contemporaneous conceptual art.

I noticed that when I got here to the west coast. There was that attraction, that falling in love without quite understanding it, of being influenced by performance, by minimalism, by the formalities that were going on. We're talking here, 40 years later, but intuitively there was that need to charge that formality with content - and content could be emotion as material, the politics of the body as material, the politics of identity. I didn't use that word, no-one used that word back then. It was Howard Fried, too, who said something that always stuck with me – "Talk about what you know..." because I think I was still lost. I have to be very honest about it: I mean like not knowing what the hell I was doing, but not stopping either. It was this search and investigation. I think those early videos demonstrate that - there's a searching, there's a turning the camera on and playing with my body, playing with sounds, doing things, not judging it, never thinking that those videos would ever be shown.

Tony Labat, Solo Flight (video stills) (1977). Courtesy of the artist.

Now there is so much of an interest in those early works. And, ironically, they're called Solo Flight (1977) - about three hours of very short gestures. It was this idea of bringing - today we can say identity - but bringing content, bringing autobiography into the work. At the same time always this thing that would hold me back, which was: but who cares about me? And so the challenge was where do I find the universal, where do I find issues that are part of being human - not so much of a particular nationality.

These gestures seem to be to do with this getting on the inside of things.

I have to admit that when I got here I knew very little art history, almost none. My schooling was interrupted in Cuba - that's another story, but it was a very political tension between my father and my mother. For two or three years I was kept away from school. I would hide during the day and in the afternoon go out and play and pretend so that the neighbours didn't see me in the streets. When I got to Florida they didn't have any kind of bilingual/ESL programmes, so I didn't even understand what the teachers were talking about. And, ironically, I would always pass (laughs) - which says a lot about the education system. I immediately realised it was a joke. I remember my report cards were fail, fail, but I would get A for effort (laughter). So when I got here everything was pretty much intuitive, and yes, to get inside of things from my own perspective and experience.

What was the response to your work as a student at the Institute? It must have been very different from your peers.

There was something perverse about that. Again, maybe the whole joder thing. There was something, a natural thing. When I would start performing for the camera, I relied on the things that were familiar to me: rhythms of sounds that relate maybe to the drums, a lot of references that I knew would be lost in the translation.I knew that I was not in Miami anymore, that I was speaking to an English-speaking audience; mostly western, mostly American. I think there was something - a perversion - about attempting to put the audience, the viewer, in my shoes. Issues of language were very important to me. I knew that the props, the gestures, that I was using would be lost; lost in translation. At the same time, I resisted translating anything. When I started using language in the videos, I would intentionally speak in Spanish. That came from something about starting from the place of knowing what was really mine, and in the process putting it in the face of the viewer to understand issues of the other. To answer your question: I was probably seen as something exotic.

But you're also playing on that.

I was one hundred per cent exploiting the exotic (laughter). Absolutely. I was using that as material.

And because you're dealing with your own situated-ness, the lost in translation element comes to describe your audience, also.

Yes. I got here in 1976. I think one thing that is important to mention is that between '76 and '79/'80 Mabuhay Gardens, the punk club, was on Broadway, just a few blocks away from the Art Institute. I was in school with members of the Mutants, the Units, the Avengers. So we would go there and see that. I was like a wallflower - I was a little bit too old to be a punk (laughs) and I was becoming too academic, too much of an observer. I really connected to the elimination, if you will, of a stage, or the attempt at eliminating a stage. I would connect it in a weird way with the mosh pit and performers jumping into the audience. I would connect it with Yves Klein jumping off a window [Yves Klein, Leap into the Void (1960)]. I would connect it to sculptors and minimalism trying to get rid of the pedestal with the floor pieces. I think that provoking the audience, the provocateur - and how the audience responded - is something that I thought, then, was ahead of art. At that time the audience in art was, in my opinion, still quite passive. Being here in this punk environment is not talked enough in terms of my work, but it was really very important in my development.

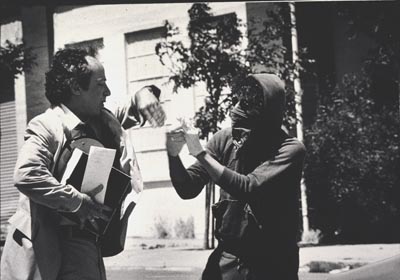

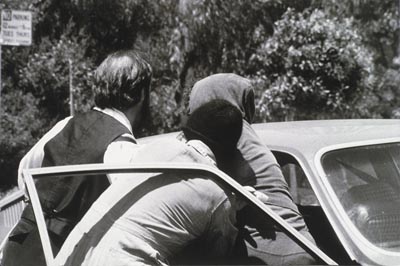

Tony Labat, Kidnap Attempt (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

Some of that seems to coalesce around a piece like Kidnap Attempt (1978).

Absolutely. Yeah. Well (laughs), you know, that same year Jello Biafra [lead singer/songwriter, Dead Kennedys] was running for mayor of San Francisco. So we have the Art Institute Studio 9, we have Mabuhay and the punk scene. At the same time - I called it Janitor: Tom Marioni says that I was his apprentice. But I was also working for Tom at MOCA (Museum of Conceptual Art).

Yes, he told me that yesterday (laughter).

(laughs) I refer to it as His Janitor. I'm very proud of that, because a janitor is like an apprentice, but I liked the title of Janitor. And most of my duties were that (laughs).

MOCA, 75 3rd Street, 1978.Photo courtesy of Tony Labat.

You fixed his roof.

I did fix his roof - in a very artistic way (laughs). I polished his sinks and I did all kinds of things. And, at the same time, I am hanging out with David Ireland.

You made a video of Ireland working on the house, in 1977?

Yes. I was there, witnessing the whole process. So I got MOCA, I got David Ireland, Mabuhay Gardens, and Howard Fried. How lucky I was (laughs).

Did you go to Tom Marioni's gatherings at Breen's Bar?

Well, it took a while, but that was one of the janitor's intentions was to get inside the lion's den. And yes, eventually, I sat at the table; eventually I did. Those things are really important in my development. It's who I am, which is not one thing but many things. I'm a cultural mutt. It's not just the confrontation, but the zen-like life/art issues that David had - issues of ephemera and temporality. Tom Marioni was influencing me. And then I would get the formality of Howard Fried. Howard Fried's work is very autobiographical. Bonnie Sherk was doing The Farm (1974-8), Mark Pauline with Survival Research Laboratories. I really did feel that if an artist wanted to open a bakery, it would be the best bakery on the neighbourhood. I never thought that art was a one-way street to the white cube.

Tony Labat, Kidnap Attempt (1978). Courtesy of the artist.

But, getting back to Kidnap Attempt and Lowell Darling. I was being influenced by punk, I was very political. I was a fucking young art student. I would look at Jello and see seriousness, even if he wasn't going to win the nomination for Mayor of San Francisco. I didn't see it as a joke: he was really bringing issues, a platform of ideas if you will, about politics in California at the time. Lowell was a jester and so I wanted to interject a little bit of social realism - a kind of social realism transferred into a gesture, an action, a performance: what would it mean to bring a kind of realism to it? It started with that. And with creating a persona. Creating a persona that had led me to the boxing in Fight (1981) and, before that, to The Gong Show (1978). Today we call them interventions, back then it was kind of like - guerrilla.

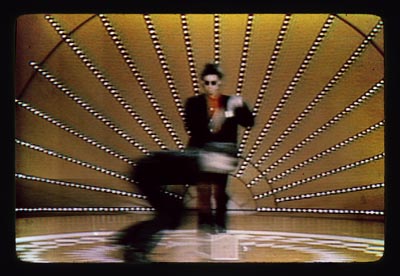

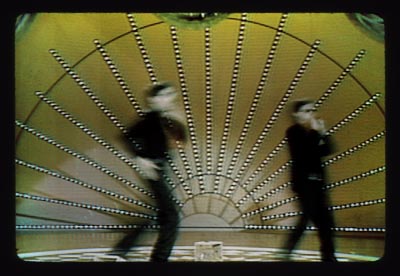

Tony Labat, The Gong Show (1978) video stills. Courtesy of the artist.

They seem like infiltrations to me.

So infiltrating into The Gong Show: not calling it art - just being on national television and get that reaction. For The Gong Show the act we did was so abstract, so absurd, so stupid, and with no talent whatsoever. That's where I think the lessons of Les Levine come back. The Gong Show was actually infiltrating a world where talent was rewarded. And Bruce Pollack and I, we said let's go - I said, we have to bring something that has no talent whatsoever, something that anyone could do, and of course the document.

Tony Labat, Fight (1981). Courtesy of the artist.

In what way?

To me all that mattered in Kidnap Attempt, The Gong show and Fight was to get that photo, the video, the document. I was very influenced by the Yippies, by Jerry Rubin wearing his American flag shirt. I was very influenced by the power of the image in the media. At the time there was High Performance Magazine in LA, by Linda Frye Burnham. It was incredible, because it was a publication where artists could send them documents of what was going on and they would print it, they would publish it - there was no curatorial thing. So I was interested in making sure that I had the image. For Kidnap Attempt for example, I designed the composition, I made sure that the photographer had the right zoom lens, that he was hiding in the bushes. Another part of the persona was from the Red Brigades, and the Sandinistas. There are references in Kidnap Attempt to the Sandinisstas - the bandana. The guns were fake (laughs).

I didn't realise you had guns.

Yes. And another thing about that piece, was that for two years I didn't tell anybody who it was. It was done under Red and the Mechanic. Because my fear was that people would think that I was jumping on Lowell's wagon, that I wanted publicity - that it was just like an art student, getting a piece of that. And that was not what it was about. I still do believe that if an artist wants to go into politics they should do it. Otherwise it was what it was: it was a piece of theatre.

If you're going to have a $1,000-a-plate dinner, where artists eat free – but only the artists come, then obviously you're staging a certain fiction [Lowell Darling, The Next Governor Lowell Darling: A Fund Raising One Thousand Dollar a Plate Dinner (1978)]. Then the action of attempting to kidnap him after an event like that situates it back into the political - you resituate him within politics, where he didn't really want to be.

Yes, exactly. Have you read the book [Lowell Darling, One Hand Shaking: A California Campaign Diary (1980)]? He devoted a whole chapter to it (laughs). I think he talks about getting bodyguards - which was also theatrical, was also fiction. He confesses the anxiety, that he started looking over his shoulder and he started being paranoid. The interesting thing, sometimes it comes up with the Fight, sometimes it comes up with The Gong Show, questions like in The Gong Show is like - what did you do? The boxing - did you win? It doesn't matter. And with the Kidnap Attempt sometimes they ask me what would you have done if you would have taken him? (laughter) And I think that that's where he blew it. If he had a little bit of a suspicion that this was a performance piece, he should have gone, he should have gone in the car. What publicity he missed.

And then he would also have handed the problem back to you.

Exactly. And then it would have been - what do I do with him now? (laughter) I was going to be the best host in the world. I was going to make him the best Cuban meals. I was going to just have him there for two or three days, take care of him and then release him.

To put somebody in a car and confine them there for whatever short period of time is potentially risky: that's false imprisonment. It makes me think about your year's training as a boxer, there's a way in which you become the fiction that you're playing with.

Yes. It may sound crazy, but if there were going to be any consequences I was ready to go to court. I was ready to be arrested. Three or four years ago Lowell said that he could still (laughter). I think there's a statute of limitation. But I was ready. I would have loved being in front of a jury or a judge or something to talk about these issues of politics and my statement - even if it failed. The hippie culture and the counter-culture was happening here in the '60s and the '70s. The Black Panthers were right here. Angela Davis was my teacher here. How could I not take these issues of an artist being involved in politics seriously? It was ridiculous to me.

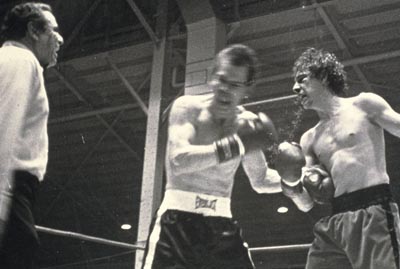

Tony Labat, Fight (1981). Courtesy of the artist.

Yes. The artist Tom Chapman wrote a letter to me challenging me to a fight. There were like a couple of camps. In the letter he alludes to me being part of a generation of artists that represented a kind of theatricality. I was performing in clubs - nightclubs and the punk clubs. By the late '70s the alternative spaces, in my opinion, were done for my generation. They had become established, they had Boards. Performance had become paying at the door - chairs were brought in. I welcomed the stage…I loved the stage.

Like 80 Langton Street.

Yes, they were kind of anti-stage - as if the stage represented some sort of theatre. To me it was a context like any other, a challenge like any other and an architecture like any other.

So that letter surprised me - in the letter he talks about a kind of theatre: that I was doing theatre; that I was just bullshit. And he ended the letter by saying: no illusion is the best illusion. I think I answered 'illusion is fine with me' (laughter).

So in his original letter he raised a fight?

A fight that had to be by the book, meaning that we had to become licensed - we had to become licensed boxers.

Which is quintessentially theatrical.

But also real, he had issues with what I represented in this new generation and in art. He was a very formal sculptor. So he challenged me to a fight, but the fight had to be by the book. And at first I was kind of like this is a fucking joke - like, I'm busy. It was flattering - I thought, man, if I'm pissing you off that much I must be doing something right. (laughs). So I considered it and then I thought, yeah, I can step into a persona, you're accusing me of being theatrical - now I'm really going to be theatrical (laughter). I accepted it. I was also very much interested and influenced by some of Howard Fried's early work, like the five golf coaches in The Burghers of Fort Worth (1975-6). There were a lot of these pieces that had to do with stepping into a certain unknown, that had to do with learning and shifting these positions of student and teacher. I had never even been in a fight in my life, not even a yard fight. So, ironically, I was interested in the craft. I was interested in learning the jab. That really attracted me. Then after I accepted it I said I'm going to appropriate the trash-talking of Muhammad Ali, who was the king of theatre. Do you know what I mean? It's just theatre. And so I became the biggest asshole (laughter). Of course, the media ate it up. I was so calculated and intentional that I had reporters almost weekly in my studio.

Tony Labat, Terminal Gym (1980-81). Courtesy of the artist.

So you turned your studio into a gym?

Into a functional gym.

Mission and First. It was across the street from the bus terminal. All the businesses were called terminal. The pharmacy was called Terminal Drugs. Everything was terminal: hence Terminal Gym (1980-81). I immediately saw the potential this had. For me the studio is where I do my work: the studio is going to be where I do my training. I was not going to go to a gym. I would make my own gym in my studio. As you know, today we call this social practice. There were two women that were boxers. In those days, women were not allowed to train at the boxing gyms here. I reached out to them and for six months they trained at my gym. They eventually became part of the card that evening. The gym became a social hangout. Paul Kos would bring his class by the gym. That was my practice. I was training, and it was the best time that I've ever had - that kind of focus and concentration. That was really, I think, one of the best aspects of that project and it is not talked enough about. Then I had to go three times in front of the California Athletic Commission and prove that I could defend myself, to get the licence. Then I became a boxer, but with this persona, and I knew it was going to be just one fight and one project.

So those three projects - The Gong Show, the Kidnap Attempt and Fight - are interrelated in many ways. Fight functioned in the media first. The night of the fight was almost anticlimactic. For me, it was the process: the gym and the media. Opening the Human Interest section and why this 30-year-old artist wants to become a boxer. Go into the Sports section and it would all be technical: can he throw a jab, can he this, can he that; how good is Labat with his feet? Then we go to the Arts section and it would be the drip of the blood on the canvas and Pollock.

I think often the relationship between performance and documentation is completely misunderstood.

Exactly. He published a book and I made a video, and that was part of the plan from the beginning - with performances I plan the documentation ahead of the execution of the piece. This interest continues with my recent work: mixing audiences, overlapping and taking things out of context. A local boxing evening like that doesn't have television cameras, doesn't have these rich-type art people streaming in, or a bunch of punks (laughs). Then the old boxing geezers were like - what is going on here?

There's the kind of displacement and puzzlement of the audience that comes across in the reports.

Exactly. That kind of confusion – that suspension of belief/disbelief. You could see the other boxers: who the hell is this Tony Labat? I've never heard of him and, look, he can't even box (laughter). There are many, many layers in that project. But I can't watch the tape.

Why?

It's so depressing. I couldn't watch it for years. I shelved it. I don't know if I ever wanted to show it. It's very personal. It's really interesting. I wanted to be good. I went into a deep depression for about six months after the fight. It was maybe normal in terms of post-blues - maybe closing down the gym was depressing. I remember going for the licence. I was obsessed with showing that I could box: showing the craft, showing a respect for the craft. I'm a huge boxing fan. I remember going for the licence in front of the commissioners and all of them would be incredibly impressed. Then we jump into the night of the fight. And I remember he hits me - he punches me in the face quite hard and everything that I had learnt was out the window. You know, professional boxers have maybe 100 amateur fights before they step into a ring with 1,000 people watching. I can't describe the emotion. It scared me, because I wanted to kill him. A lot of my early work also dealt with cultural deconstructions of machismo and maleness. So I was very interested in understanding and deconstructing that. When he punched me and I lost my cool I all of a sudden experienced what I was trying to talk about. I was also influenced by George Plimpton, Norman Mailer and the idea that if you want to write about something or understand something you have to infiltrate it: put the gloves on. This idea may be connected with social realism again. That's why I couldn't watch the tape - those emotions took over.

Tony Labat videorecording David Ireland working on his house, 500 Capp Street. Courtesy Tony Labat.

The term 'social sculpture' is often associated with Joseph Beuys' work. I noticed that David Ireland's house at 500 Capp Street has within it explicit references to Beuys. Did that association come from David?

From Tom Marioni. At least speaking for myself. Tom brought that idea in his own way to San Francisco and the Bay area. He advocated it. He talked about it a lot. So as an art student he made me very curious about what the meaning of that idea was - not so much Beuys himself. I felt what Tom did was a kind of translation - a different way of looking at it that could be more universal. One that you could adapt and define in your own way.

Tony Labat, Peace Sign (1987), Oakland Muserum installation. Courtesy of the artist.

And the Peace Sign was much later, wasn't it.

Yeah, 1987.

And you've done that in a number of variations?

I've done four of them. It's a work that I think functions in the media, functions in the newspaper, functions in the controversy. In '87 it was the twentieth anniversary of the Summer of Love. I riveted it like aeroplane wings and polished aluminium, because my idea was to give it a military, corporate makeover. Its designer Gerald Holtom refused to copyright it so that it would be available - that took care of the authorship issue.

So we move to '97 and Stanley Gatti, the commissioner, approached me. That was supposed to be a permanent one for the Golden Gate Park and that's the one that blew all this publicity open from New York, everywhere, everywhere on the press. It was at a time when gentrification was coming. The best headline about the work was in the New York Times: San Francisco does not give peace a chance. The story was that it's not mine: I didn't make anything, I didn't do anything, I didn't design anything. Why is this art? Gentrification was an issue in the politics of the work too, because Peace Sign would attract hippies, it would attract drugs, it would attract the kind of element that would ruin the real estate prices going up. It was kitsch. And, again, that's why I wanted to do it, especially because of that. And it was finally shut down.

So then in response to that I did a version that is kind of like a Hollywood front, to make a sort of metaphor for this kind of thing. And that was shown at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Then, it's a long story, but after the show was over the Moscone Center wanted it. As you can imagine, it was one of the most popular tourist pictures in front of Moscone. Then the invasion of Kuwait came and I get a call from Moscone - get the Peace Sign out of here.

So for me really it's such a trajectory, from '87 – from being kitsch to being dangerous again. I love that about that work. Now people are using it as a magnet to protest. That version is at the di Rosa Foundation now. Then in 2007 we have the 40-year anniversary of the Summer of Love. The city wanted me to do a temporary one. This time I was very successful in making sure that all the press talked about nuclear disarmament. So between Kuwait and Afghanistan and Iraq and everything that was going on after 2003, the piece then becomes important again. It was just supposed to be there for six months. This time we moved it to Hayes Valley and the whole Neighbourhood Association wanted to keep it, permanently. But that didn't happen and the Oakland Museum bought it.

Right, so it's now installed at Oakland, isn't it?

It's in Oakland. It faces the Courthouse. It's in the perfect spot.

So it's like a durational work, whose meaning keeps changing. It's all about how it articulates a public political sphere through the media in various ways. In that way, it's completely consistent with the performance work, isn't it?

I think so. I think so, whether it's performance in terms of the body or performing in the public sphere; in the media. It is linked very much to performance.