Paul Kos

Interviewed by Nick Kaye, by email 19 October 2015

Follow the links for discussions of: Lot's Wife (1968) | Participation Kinetics (1969) | Richmond Glacier (1969) | Kinetic Capsules (1969) | The Condensation of Yellowstone Park Into 64 Square Feet (1969) | Kinetic Ice Flow (1969-2013) | Quid Pro Quo (1970) | The Sound of Ice Melting (1970) | rEVOLUTION (1970) | Roping Boar's Tusk (1971) | NY Pool Hustle (1972) | San Francisco Performance (1972) | A Trophy/Atrophy (1972) | Revolution: Notes for the invasion, mar mar march (1972-73) | Pilot Light/Pilot Butte (or, The Alchemy of Ice) (1974) | Ice Makes Fire (1974-2004) | Riley Roily River (1975) | Tokyo Rose (1976) | Sirens (1977) | Lightning (1977) | Ramp (1980) | Sympathetic Vibrations (1986) | Brieftauben (1987) | Guadalupe Bell (1987) | Fraulein Oetzi Glacier (2008) | Diminuendo/Crescendo (2013) | All Is Well Bell (2015) | First Responder Plaza (2015)

Q: Your first solo exhibition at the Richmond Arts Centre in 1969 was Participation Kinetics. Why did you choose that title? What significance did the experience of participation have for your work at that time?

PK: Participation Kinetics (1969) was chosen because I wanted to make an exhibition where the viewers were invited to become active participants in many of the kinetic sculptural works.

Paul Kos, Participation Kinetics bumper sticker (1969). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Participation Kinetics bumper sticker (1969). Courtesy of the artist.

For instance, the mailed invitation for this show at the Richmond Art Center was a bumper sticker that stated Participationkinetics. If recipients attached the bumper sticker to their car, they become active participants even before seeing the exhibition itself. Prior to this piece, bumper stickers were normally used to support a politician running for office.

The first major sculpture one experienced on arrival at the Richmond Art Center was the main door being blocked by my Richmond Glacier (1969), which was comprised of 7000 pounds of ice and a few blocks of salt.

Paul Kos, Richmond Glacier (1969). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Richmond Glacier (1969). Courtesy of the artist.

My intent was that viewers would either use a side door to the museum or wait until the glacier melted which would have been some days hence. The curator of the show, Tom Marioni, and I were surprised when the Richmond Fire Department showed up at the opening, flashing lights on their fire truck, firemen in their fire gear and axes, and they proceeded to chop my glacier into small ice shavings because I had blocked the main entrance\exit and means of egress to the building. I could not have contrived a better scenario. Truly participationkinetics!

One other participation piece where the city became involved was Kinetic Capsules (1969). Next to an office water cooler, complete with paper cups, I placed a few hundred capsules that could be swallowed. Each contained a small piece of water-soluble paper and food dye with 'e=mc2' inscribed and a small stainless steel ball bearing. The Richmond Health Department made me remove the ball bearings fearing that one could lodge in the digestive track if ingested. The piece was to end when a 'plink' was heard in the toilet.

Paul Kos, Tokyo Rose (1976). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Tokyo Rose (1976). Courtesy of the artist.

In essence, these early pieces led me to try to compose equilateral triangles comprised of the artist, the object, and an active viewer. I never, ever allow wall instructions like: 'step between the planks' (Revolution: Notes for the invasion, mar mar march [1972-73]) or 'enter the cage' (Tokyo Rose [1976]), or 'ring the bell' (Guadalupe Bell [1987]), or 'place the ball in the hole' (Diminuendo/Crescendo [2013]) etc. Either the piece has enough bait to entice the viewer to participate or it is left incomplete.

Paul Kos, Guadalupe Bell (1987). Courtesy Paul Kos.

Guadalupe Bell (1989) is a 500-pound bell with a long rope attached to its clapper. The rope extended well into the museum space. If, and only if, a viewer pulls on the rope does the Virgin of Guadalupe appear on the wall next to the bell. This apparition lasts only as long as the hum note of the bell. No instructions are allowed therefore a viewer has to decide whether a large bell alone in a room with a long rope is worth tugging even though normal museum policy tells one not to touch the art. Not everyone is granted an apparition.

Paul Kos, Guadalupe Bell (1987). Courtesy Paul Kos.

Q: Which artists were influential on the development of your early work? Has Arte Povera been significant to your work?

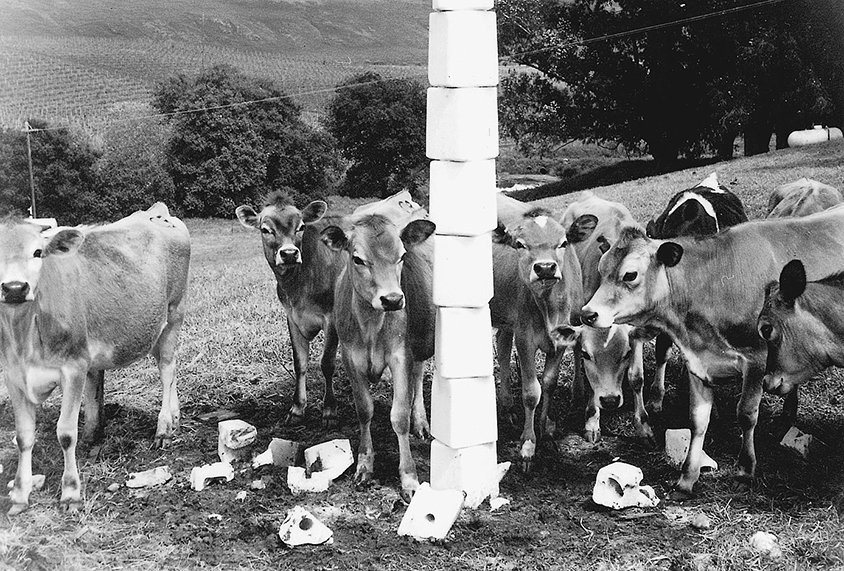

PK: Originally, I began to use salt and later ice out of exasperation: that is, I had been working with resins, polyurethane foam, fiberglass, and lacquers, and suddenly felt that with all these toxics I was working against the grain. I made Lot's Wife (1968) out of salt blocks so that the cattle on the di Rosa Art Preserve could lick her away.

Paul Kos, Lot's Wife (1968) (detail). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Lot's Wife (1968) (detail). Courtesy of the artist.

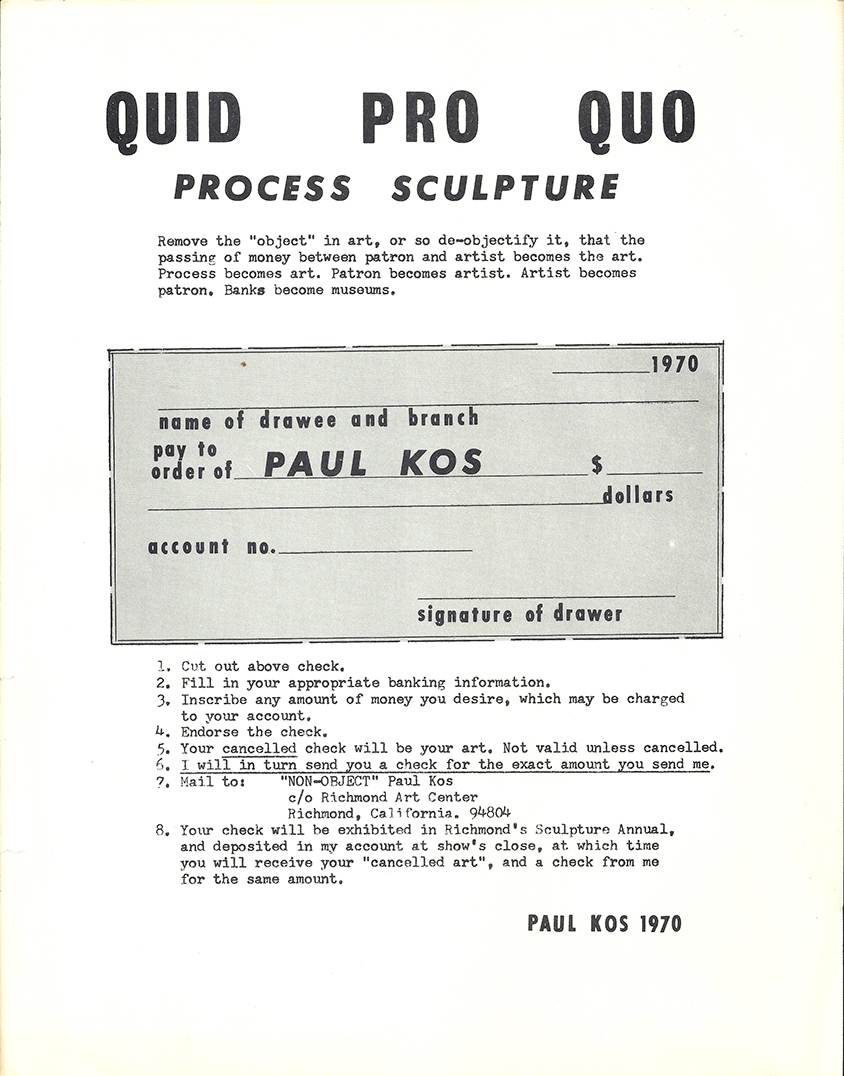

I thought I was working alone in this direction in 1968 but shortly after I met Dennis Oppenheim, who also had a piece in the di Rosa collection, and Tom Marioni at the Richmond Art Center who gave me my first solo show described above and included me in Return of Abstract Expressionism where I made The Condensation of Yellowstone Park Into 64 Square Feet (1969). Later, for the Richmond Sculpture Annual, I presented Quid Pro Quo (1970),where I met Terry Fox. When Tom was no longer the curator at the Richmond Art Center, he started the Museum of Conceptual Art. He was an ingenious artist/curator instigating early 1970's exhibitions, throwing out a title, inviting artists working in similar veins of Bay Area early conceptualism to make pieces relevant to his titles which I thought were like assignments and I was thrilled working within his parameters. Subsequently, I became friends with Terry Fox, Howard Fried, Sharon Grace and Bonnie Sherk.

Paul Kos, Quid Pro Quo (1970). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Quid Pro Quo (1970). Courtesy of the artist.

Terry Fox traveled to Europe quite often and brought back stories of Joseph Beuys and the Italian artists working within Arte Povera. Kounellis, Pistoletto, Fabro, Merz and others became inspirations and so to speak, comrades in arms. We all responded to simple, humble materials for their simultaneously obvious and hidden complexities, whereas New York conceptualists were often more interested in language based work with the exception of Bruce Nauman who was a favorite of both coasts.

Q: You originally came from Wyoming and have in the past periodically returned there to make your work. What does the experience of this place offer to your work or process?

PK: Growing up in Wyoming had a big influence on my work. It is the seventh biggest state with the least population. Over 90% of the land is public and so it became my studio after I began conceptual work in 1968. I didn't have a real white cube studio space until about 1984 and so driving 'to and from' and the landscape in those early years generated most of my ideas. I had worked on a ranch and knew of salt blocks for livestock; lassoing was expected, lightning could be called upon to perform, rivers were riley or roily, volcanic cones, distant buttes, and coal and ice were waiting to become defining elements of my work. It was as if I could call out: 'Ford here, Herefords!' and the cattle would cross the river on command.

Paul Kos, Roping Boar's Tusk (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Roping Boar's Tusk (1971). Courtesy of the artist.

One of my precepts is 'Respect site or be short-sighted'. Over a period of years in the 70's I made, as inspired by site, Roping Boar's Tusk (1971), Sirens (1977), Lightning (1977), Riley Roily River (1975) etc.

Q: What is the role of accidents or the accidental in the creation and experience of your work?

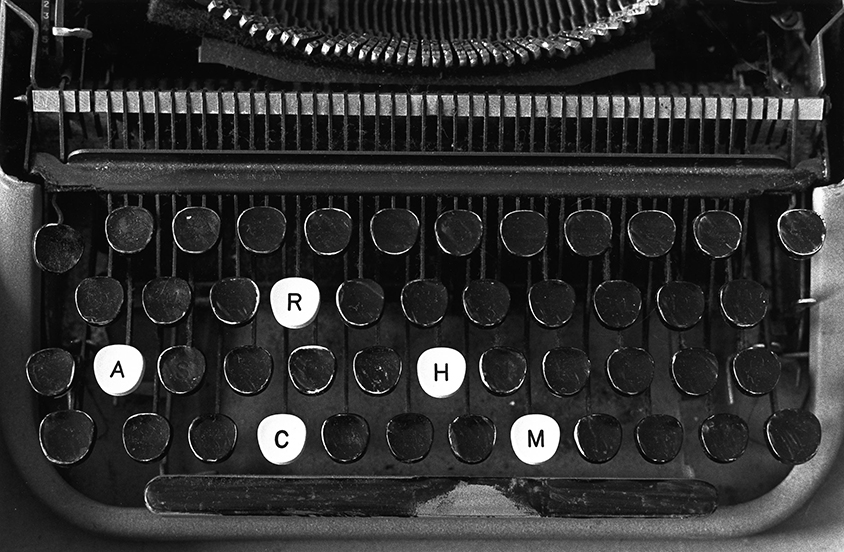

PK: Another major influence for generating ideas was not what I could contrive on my desktop, but being open and receptive to 'accident' to lead the way. For instance, one evening in 1972 while typing a syllabus for a class on an old Smith-Corolla typewriter, I happened to see on the TV a documentary of Leni Riefenstahl. German troops were marching and I found that I could duplicate the 'ta ta tum, ta ta tum, ta ta tum tum tum' of the drumbeat, by typing 'mar mar march mar mar march.' Had not the screening of this film taken place while I was typing, I would never have thought of this concept. What I like most about the piece is that it is an onomatopoeia, it sounds like it looks and looks like it sounds. This piece is titled: REVOLUTION, Notes For The Invasion: mar mar march (1972-73).

Paul Kos, REVOLUTION, Notes For The Invasion: mar mar march (1972-73). Courtesy of the artist.

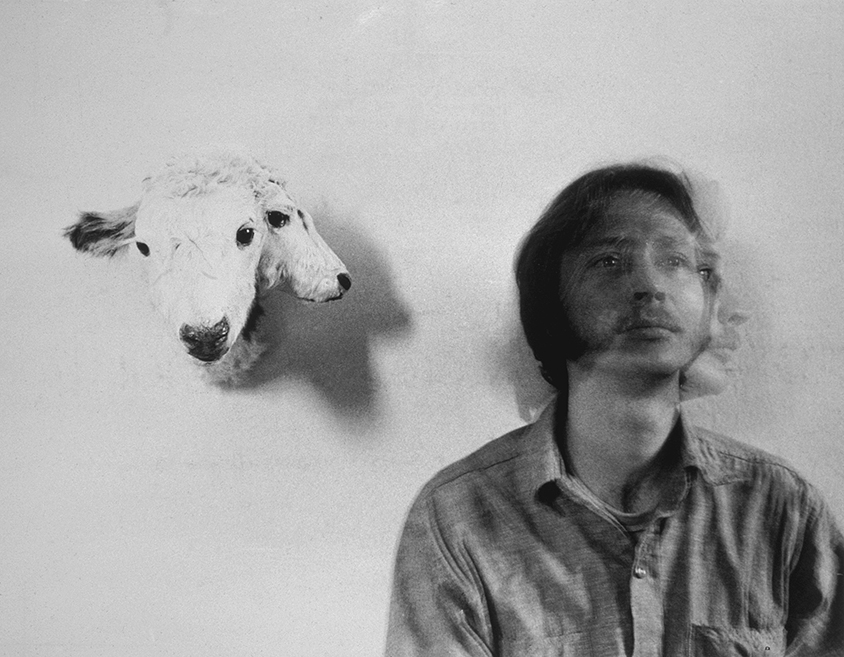

Another example of the accident finding me occurred during a visit to Wyoming. A rancher friend had had a calf born with two heads. The calf died when the second, smaller head atrophied. The rancher sent the double-headed calf to a taxidermist.

Paul Kos, A Trophy/Atrophy (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, A Trophy/Atrophy (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

For a 16mm, b&w film, with my head next to the trophy, I turned my head frame by frame, looking forward then left, forward then left, faster and faster while reciting, 'a trophy/atrophy, a trophy/atrophy' faster and faster until I had two blurred heads and the 'a trophy' atrophied in a mumble. The piece is titled A Trophy/Atrophy (1972).

Q: You have created a number of early works that incorporated actions or performance – I am thinking of rEVOLUTION (1970), NY Pool Hustle (1972) and Ramp (1980) - as well as participating in Tom Marioni's San Francisco Performance (1972). In works such as these what was it that interested you about actions or live events?

PK: Early in the late 60's and early 70's I generally performed for film or video and only four or five times for a live audience.

For example, Roping Boar's Tusk (1971) was done for film only as the setting was a very remote 400-foot high volcanic plug in southwest Wyoming that I tried to lasso.

Paul Kos, rEVOLUTION (1970). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, rEVOLUTION (1970). Courtesy of the artist.

rEVOLUTION (1970), a live performancewas comprised of an invisible weight exchange from artist to target via a shotgun and 40 pounds of small arms ammunition. I was on a scale and the target hung from another scale. Over a period of 90 minutes I lost 40 pounds, while the target gained weight as it accumulated the lead pellets in the beginning but lost weight as it was itself blown apart. Many viewers were in attendance and they said they felt like they were watching the Crimean War as they were invited to the di Rosa Art Preserve site by Rene di Rosa for a buffet and wine tasting on the balcony of the main house. The view from there was that of newly planted vineyard with only the stakes visible and looked like a military cemetery. Also, live closed circuit video of the performance was piped into the living room of the house, resembling instant news coverage. This was during the War in Vietnam.

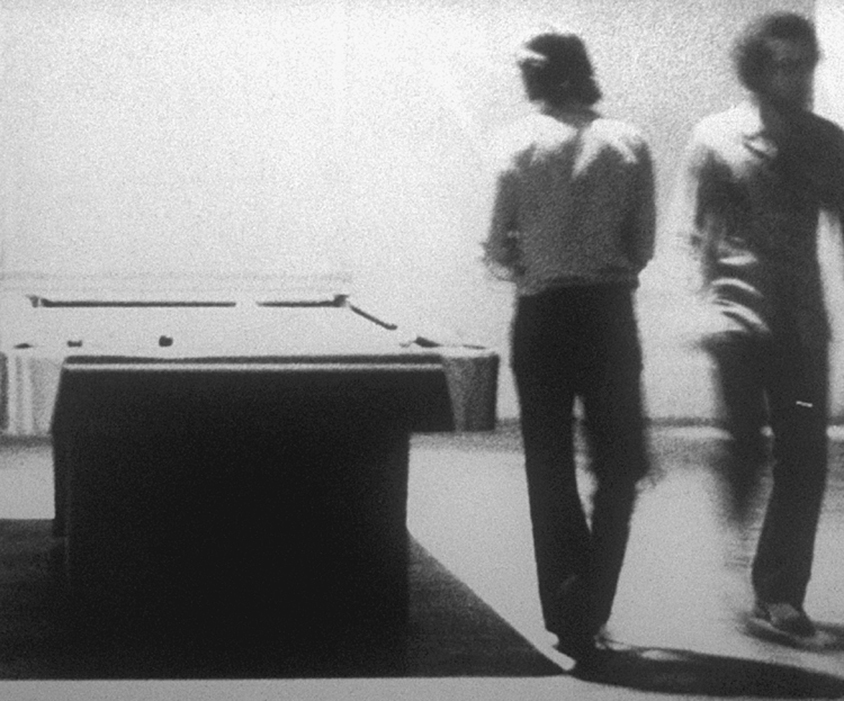

In San Francisco for about six months, I religiously practiced pool. NY Pool Hustle in 1972 was a live performance at the Reese Palley Gallery in NYC. For the performance, I also made a Super 8mm film loop of sheep being docked (castrated) on a ranch in Wyoming.

Paul Kos, NY Pool Hustle (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, NY Pool Hustle (1972). Courtesy of the artist.

In New York, I went to the billiard hall where the film, The Hustler, was shot with Paul Newman and Jackie Gleason as Fast Eddy and Minnesota Fats. At the reception desk, I asked who was the best player there at the time, the receptionist gave me an evil stare but looked at a fellow in a white suit sitting near a pool table. I went over to him, and said, 'there is a Rolls Royce waiting downstairs and a pool table in a gallery and if you would play me, the gallery would pay for my losses.' He went to a locker, took out a small case with a three-piece cue and we went off to the gallery. He commented that his cue cost more than the table. This man in a white suit, looking like Thomas Wolfe, proceeded to beat me game after game, sometimes running the table, not giving me even one shot. He kept uttering that he could have been a psychiatrist given the time it took to play so well. All this took place while the sheep were loosing their balls on the film projection. I could not have scripted a better performance.

Paul Kos, La Boule d'Or (1985) Civic Centre, San Francisco. Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, La Boule d'Or (1985) Civic Centre, San Francisco. Courtesy of the artist.

After art installations with pool and chess came and went, my new addiction is the French game, Boules or Petanque. I have built about eight courts, three in the art context. It is one of the fastest growing games worldwide, it is played everywhere the French colonized and now in the US and England it is spreading like a virus. Again viewer participation is absolutely required. Curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist wanted to interview painter Gerhardt Richter. Richter agreed on the condition that Obrist would play Petanque with him and a few of his friends. The Queen of Madagascar made the game the national sport and kids six years old and up play it in school. This past year the women's team from Madagascar beat the French in the world championship. Why is this art one could ask? My response is this story. Napoleon took a young artillery gunner into a field and told him to aim and hit the distant target. The nervous private loaded the cannon - and fired. The cannon ball was short. Napoleon told him, 'No Problem, try again.' The private loaded again with more powder, aimed higher, fired and this time the shot was long. Napoleon held a pistol to the private's head, and said, ' you now have the long and short of it, fire again!' The private aimed, adjusting the cannon, and hit the bulls eye. In Petanque, one plays with three balls, and there is no excuse that one is not a carreau (a direct hit). In art making, when and if we are out of shape, we often copy our last, best piece, and it falls short. We then over compensate trying to really go for it and make something not credible to others or even to our self. The third time we may meet the exact place where culture and significant research come together. Success! 33% is not a bad average, in any endeavor.

Q: You first incorporated bells into your work in Sympathetic Vibrations (1986) – and subsequently in a number of installations and public art commissions. What brought you to incorporate bells into your work and what significance do they have for you?

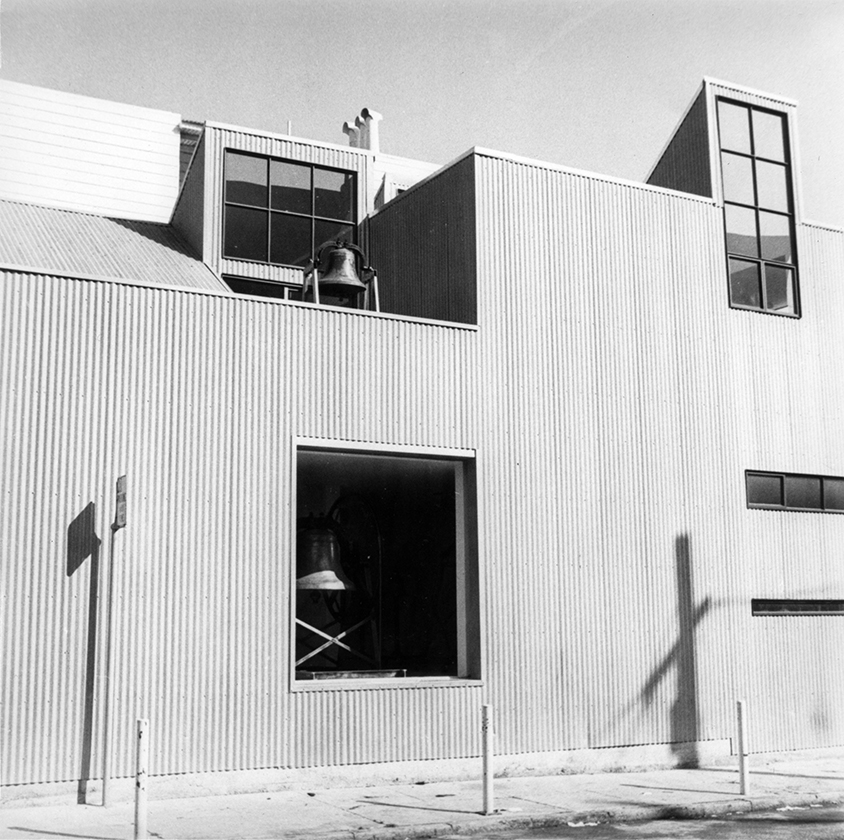

Paul Kos, Sympathetic Vibrations (1986). Courtesy of the artist.

PK: Yes, Sympathetic Vibrations (1986) was my first bell piece. I had been given the Capp Street Project and found the site in the Mission district of San Francisco to have two types of graffiti: the normal visual tags and uninvited audio graffiti. Boom boxes were the rage as were loud, low bass speakers in supposedly 'cool' automobiles. I questioned, 'What were the earliest forms of audio trespass?' Drums and bells! So I decided to rent and borrow eight bells, the largest being 1000 pounds and the smallest 20 pounds. Together they rang a harmonic cord and my friends and students at SFAI helped me ring them daily at noon for about three minutes for one month using a Slovenian bell ring that I learned as a kid in Wyoming. The neighborhood thought there was a new church in town, but these were real bells that could be seen from the street, not the tape recordings that most churches had adopted. Viewers/listeners came into the Capp Street building and felt the vibration of the ring traveling up their bones. I was grateful that the neighborhood liked and appreciated this uninvited sound. I respect a bell for its role as an instrument and its highly aesthetic, sculptural form.

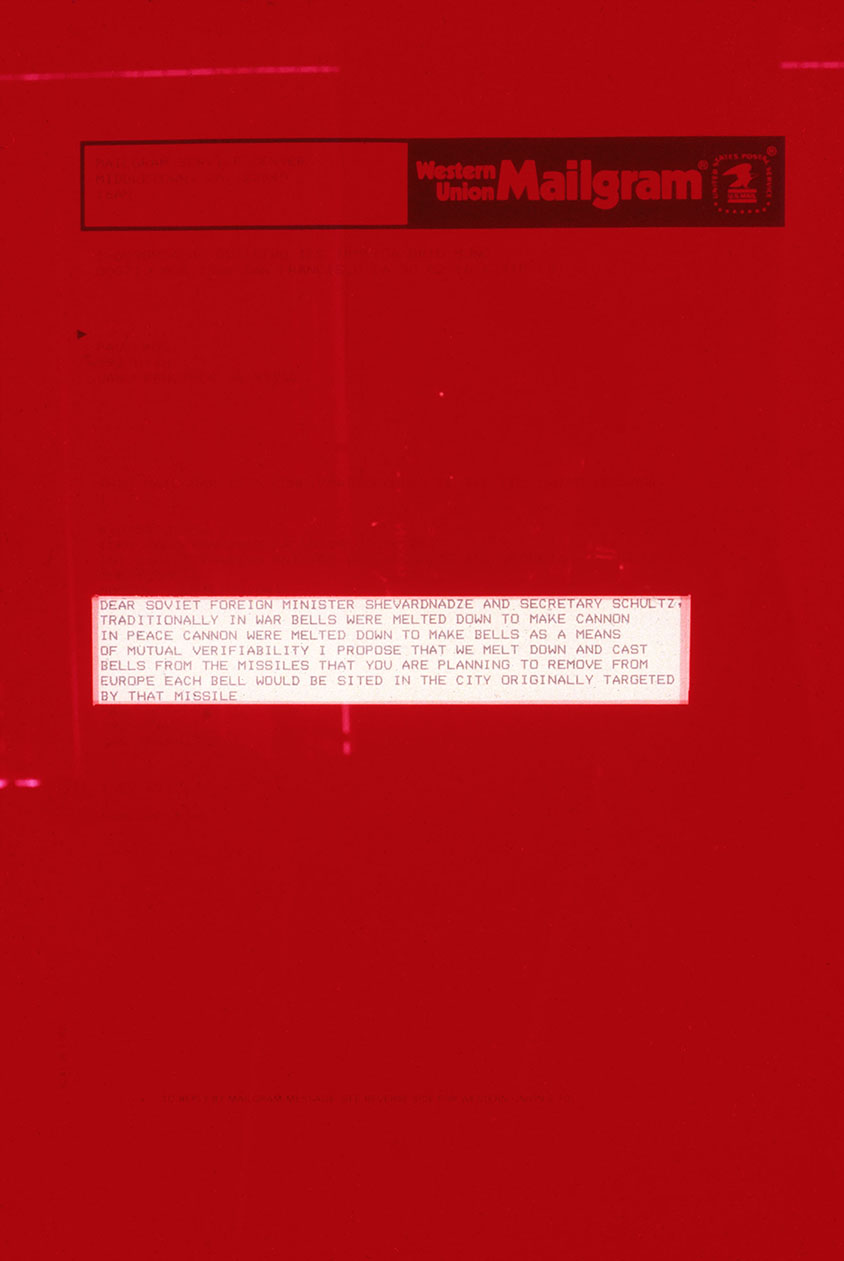

Paul Kos, Brieftauben (1987) mailgram. Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Brieftauben (1987) mailgram. Courtesy of the artist.

Many other bell pieces followed including Brieftauben (1987), where I trained 100 homing pigeons to carry a bell on one leg and a small Soviet or US flag on the other and released them from several countries of Europe and all of them flew back to home in the museum in Graz, Austria. They were metaphors for the short-range missiles Reagan and Gorbachev were removing from Europe. From release point to target the mission was successful.

Paul Kos, Brieftauben (1987). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, Brieftauben (1987). Courtesy of the artist.

The most recent bell piece, the All Is Well Bell (2015) is part of a public art commission: First Responder Plaza (2015) for the new San Francisco Public Safety Building.

Paul Kos, First Responder Plaza (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Kos, First Responder Plaza (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

For this outdoor, publicly accessible plaza I chose three major elements hoping each would serve double duty: a tall Spruce to act as a natural flagpole; a 20,000 pound bronze bell, which rings daily a D below middle C, at 20 seconds before noon, at noon and 20 seconds after noon stating, 'all is well,' and finally a 10 foot diameter, seven point, black granite police star that serves as both sculpture and seating.

Q: You have frequently returned to using certain natural and temporary materials – for example ice in Richmond Glacier (1969), The Sound of Ice Melting (1970) and Pilot Light/Pilot Butte (or, The Alchemy of Ice) (1974). What is the significance of such materials for you?

PK: Currently, while a resident at the Rockefeller Center in Bellagio, Italy, I am working on The more coal burns, the more ice melts. Since 1969, I have used ice as a material in many installations and video pieces: The Richmond Glacier (1969), The Sound of Ice Melting (1970), Pilot Butte, Pilot Light (1974), Fraulein Oetzi Glacier (2008), Ice Makes Fire (1974-2004), Kinetic Ice Flow (1969-2013).

Paul Kos, Ice Makes Fire (1974-2004). Courtesy of the artist.

As a substance ice is magical. It is simply liquid water or water vapor trapped below freezing temperatures. Scientists of climate change are warning that if we burn coal excessively there will be no more ice in glaciers or at the poles. Art-Mecca, New York City, will be underwater! Wake up! Listen to the canary!