Janet Delaney

Interviewed by Nick Kaye, Berkeley, 30 April 2015.

How did South of Market 1978-1986 originally come into being?

When you ask me that question, I see ideas coming at me from various points. Nothing was totally linear. Here is a bit of background for how I started this project. I had earned an undergraduate degree in photography from a fairly traditional school, San Francisco State University, but I found the conceptual artist, Mel Henderson, there in the sculpture department, so I had the seeds of conceptually driven political art in my education. I'd started to learn colour, which wasn't seen as serious in the mid-'70s and was not encouraged in the photo program. Colour photography was just coming of age in a way. But I saw it as essential to documentary work.

After I graduated I was often in conversation with Lou Thomas, Donna Lee Phillips, Hal Fisher and Meyer Hirsch. We discussed semiotics and language, trying to find the point where photographs could or could not provide meaning. This idea of structuring your work around ideas, as opposed to formal elements, felt prescient. The idea of infusing fine art with a sense of social purpose also remained very important to me.

Did you feel at that point that your work was close to the conceptual artists?

I was intrigued, but I still had this very traditional background in making beautiful objects, perfectly produced prints were the gold standard of my education. I have always been a "maker", to use a contemporary word, so making a beautifully crafted print was always important to me. At this time I was working hard to prefect my technique in color printing. It was very difficult to control the materials in the beginning. Lab work was super tedious.

I graduated and I flailed about, as one does. I was thinking about semiotics and talking to these people and watching the conversation unfold. I felt I needed to learn another language; this was my literal take on understanding semiotics! So I went to Mexico and Central America. I pretty much just had a bus ticket and I took off by myself. I brought a medium format camera and a tripod and a lot of colour negative film. I bought a one-way ticket and I didn't know when I would be back. I was gone for about six months. That was a defining journey. On this trip I took on the task of learning Spanish and I actually became quite fluent. I studied in Guatemala and became completely immersed in the life of one family there, which seems to be the way I work. It wasn't easy, but it was very purposeful for the idea of language and photography. However, I didn't realise I was going right into a civil war.

What date was this?

I went in January of 1978. I got off the bus in Managua and there's the National Guard driving through downtown, soldiers standing side by side in the back of a truck with their guns raised - civil war: now that's another thing to think about. I didn't stay in Managua long, but I did get a feel for what was happening. I was mainly in Guatemala, where there was also a lot of fighting going on; and in El Salvador as well. I went there with a very specific fine art perspective. I was still photographing blank walls, in a minimalist style - like Lewis Baltz. I was still struggling with new formal Topographics; ideas that I'd been inculcated with in my undergraduate programme. But I was experiencing the world in a very different way. I was learning about social upheaval, revolution and seeing the United States from a new perspective.

Janet Delaney, Laura Graham, 62 Langton Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Laura Graham, 62 Langton Street. Courtesy of the artist.

When I came back six months later it was very difficult to find a place in San Francisco. I don't know exactly what the forces were that made renting so complicated; I know that there was no rent control at the time. I had this illusion about loft living from visiting friends in SoHo in New York City. But I ended up in a little apartment on Langton Street, between 7th and 8th and Howard and Folsom Street. The rent was $250 a month which was 100% higher than it had been for the former tenants. So rents were going up, space was limited. I shared the apartment with a filmmaker, Laura Graham. Though many artists were living in warehouses in this area, we elected to move into this little three-bedroom apartment. It was minimal, but I immediately seized one of the bedrooms and turned it into a darkroom. I did the plumbing, put in a sink and I got to work printing my colour photographs from Central America.

And you were living more or less next to 80 Langton Street?

Right next door pretty much. We were at 62 Langton. I occasionally photographed the performance art pieces that were staged there regularly.

I had an exhibition of the work that I'd done in Central America [Managua, Nicaragua 1985] in Open Studios, held in Jill Scott's studio across the street from me at 71 Langton St. I wanted to improve my colour printing, and so somebody introduced me to Meyer Hirsch another conceptual artist who in turn led me to Steve Zeifman who owned Frog Prince, a photo lab. I worked there full-time as colour printer for about three years. We were printing all the artists' work as well as a lot of high-end advertising work. That really gave me a lot of experience. When that job ended I set up my own colour lab in earnest in South of Market, I bought a colour processor and installed it in the bedroom/lab of our apartment.

Janet Delaney, Tom Whiting and Ted Haacke's kitchen, 58 Langton Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Tom Whiting and Ted Haacke's kitchen, 58 Langton Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Even after my return from my travels south I was still photographing blank walls and just looking at form. I was young and in the midst of a lot of transformation, so I was looking for ways to make images of that sensibility. I was photographing any sort of construction site I could find from empty warehouses to the new extension of the San Francisco airport. I was working alongside Catherine Wagner. We would go out to construction sites in the outlying area - to Petaluma or Oakland or any place where new development was happening. There was still a lot of suburbia that was being built out at that time, and the exodus from the cities to the rural areas resulted in filling the landscape with this kind of sprawl. That was a topic that photographers were pretty fascinated with. Then Catherine said, well, there's one just down the street from where you live. I went over there and I thought: Whoa, what happened here? It was 20 acres of land that had been cleared in the late '60s, early '70s; 4000 residents and 700 businesses had been removed. Then it had remained an empty lot. For ten years! Why?

Janet Delaney, Moscone Centre under construction. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Moscone Centre under construction. Courtesy of the artist.

Suffice it to say it was this huge, abandoned place in the middle of my neighbourhood - and I was able to easily access it because I lived nearby. They had finally started to build on it after a ten-year hiatus. On the weekends I snuck under the fence - and brought my view camera and started taking pictures. I was fascinated formally by the rebar, but ultimately understood that the neighbourhood would be highly impacted. I decided I wanted to photograph what was gone. Which is a problem that I've often tackled: try to photograph nothing, photograph something you can't see. I began the South of Market project with that idea in mind. I saw one building being torn down at night and that became a very big impetus for me. I saw the wallpaper and I thought of the people who had lived there. And from there, I began to read Chester Hartman's Yerba Buena: Land Grab and Community Resistance in San Francisco [1974]. It was a history of how this working-class neighbourhood had been turned into a slum and then ultimately demolished to make way for the Moscone Centre. In some way it tied into the politics that I'd been learning in Central America. And all of a sudden everything just started to come together. I was no longer a formalist making content-less photographs. I had a mission to bring out the narrative of the people whose lives were being directly impacted by the arrival of this huge convention centre in their community, and in turn causing a great deal of displacement. At this point the word 'gentrification' hadn't yet been articulated or fully understood.

You also recorded the voices of the people you were photographing.

In the Fall of '79 - I'd started at the San Francisco Art Institute as a graduate student – and I met Connie Hatch. She was a year ahead of me and showed me a piece she had done on her brother, who was a lineman in Texas. She photographed him and recorded him talking about his work and his life. She made a two-projector slide show with audio. I was so moved by this method of storytelling. It was personal and intimate. The internet has been this amazing equaliser, where everybody's a star, right (laughs) - here's my picture, you know, here's my story. But at that point it wasn't normal to hear this personal narrative. I was reading Studs Terkel's book, Working [Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1975)]. The idea of the 'personal as political' really struck me as the way I wanted to go.

I made a very similar project with my father, who sold beauty supplies. He drove all around Los Angeles, selling beauty supplies to the shops, making calls. I travelled around with him for a week. I documented him giving his pitch about the act of sales and beauty and the beauty industry. It's like: 'I've got a case of perms bouncing around in the back of my car for two weeks, I'll give them to you cheap'. He was a really amazing person in the way he interacted with 'his girls', as he called them. That's what I'd grown up with. I stopped the South of Market project for a moment – in the spring of 1980 - and I did this project about beauty and capitalism and I turned it into a two-projector slide show.

Janet Delaney, Langton between Folsom and Harrison Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Langton between Folsom and Harrison Street. Courtesy of the artist.

I decided to use this same approach with my neighbours for South of Market – I began talking to the people who were residents. I started by recording my neighbour Jill Scott - she's a conceptual artist. She taped herself to the side of the wall across the street from Langton with some kind of heavy tape, and stayed there 24 hours [Jill Scott, Taped (1975)]. And I also spoke often with the artist Jim Pomeroy who lived just above 80 Langton.

So how is this pertinent to art in the '80s? I think for me personally what was fore-grounded was the idea of putting political action in the fine art arena: could I make politically active work by paying attention to the voices of the people who lived and worked South of Market? I didn't want it to be like a gritty black-and-white documentary of poor people. My intention was to highlight how these people are really worth something. I was asking how could you have just demolished their lives? Here are those who remained; is there a way that we can try to bring more awareness to city planning? We should not just bulldoze over poor neighbourhoods through the powers of finance and the bank. I met with a group called South of Market Alliance, who were likely Marxists. Being raised in a very capitalist country even the word socialism was somewhat suspect, but I had to think about this stuff from my own perspective. The South of Market Alliance was trying to get the Moscone Centre - which was called the Yerba Buena Centre until the then mayor of San Francisco, George Moscone, was murdered so they memorialized him with a convention centre he had opposed - to hire local residents. Simple: hire from the neighbourhood. Now, there are laws that say you have to hire locals, even new grocery stores are touting this practice. So, concepts that were somewhat newsworthy then are here, now, 30 years later. At the time, that was pretty radical. It was optimistic, but frankly a lot of the things we were talking about then have happened.

I came to San Francisco during the Summer of Love. I was 14 when I came to the Haight Ashbury for the summer to help my sister with her new baby. I was blessed to have the opportunity to experience my first city in this magical, absolutely transformative time, 1967. I thought that was what the world was like. I thought you grow up; you play in the park on Hippie Hill (laughs). So having watched the arc of the city over all this time, and seen some of the really amazing things that have come about has been great. But I also when I think about that Summer of Love and what was going on simultaneously. While I was playing in Golden Gate Park the developers were tearing down the Fillmore District, home to a large African American community and then tearing out the heart of the South of Market where seniors lived in residential hotels. This was all happening at this same time.

I wanted to make my work in the service of the people who lived and worked in South of Market, and to do it in a way that was beautiful enough so that people would look at it, thus I made large format colour photographs. Frankly I was not thinking about conceptual art. Conceptual art is wonderful for artists to make and share - but hardly anyone else ever understood what the intentions were, it seemed like artists were talking only to each other. I wanted a more public interaction. There were other artists who were grappling with these same challenges and trying to broaden the audience beyond the established intellectual crowd. But in hindsight I think the motivations for breaking new ground in art, for making art that could be defined in broader terms, laid the groundwork for social political work. So I retract my initial rejection of 'conceptual art' and actually embrace it spirit of it!

Janet Delaney, Langton Street between Folsom and Howard Streets. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Langton Street between Folsom and Howard Streets. Courtesy of the artist.

Using colour seems very important to a sense of emotional connection to the image - and the detail of these individual worlds is a very powerful draw.

Yes. I couldn't understand why I would abstract things, particularly from the point of view of a documentary. Which is ironic because people were like, you're doing a documentary? You shouldn't do it in colour. It seems so archaic to even have those thoughts now. Colour was very important to me personally, because it gave all the information. At that time I knew the work of Richard Misrach, who was working in colour - I was printing some of his photographs at Frog Prince. I'd seen Camera magazine with a few Stephen Shore photographs. I knew Joel Sternfeld's work. Camera Magazine would come once a month and I'd pour over it. Larry Sultan was also my professor at the Art Institute and he was working in colour at that time though not documentary at all. And Reagan Louie was also working in colour. So it was really happening in that regard; it seemed like the place to be. Black and white for documentary work seemed to add mystery to the subject, to distant it.

How did you approach the people or communities for South of Market?

I knew I wanted to have a representation of different kinds of activities that were going on in the neighbourhood. So I would head out each day and wander into shops, auto repair garages, casket factories, cafes. I was nervous, even shy, but I really wanted the photographs so I pushed myself to talk to strangers. I never made appointments. I only photographed what I found on my walks.

Initially I started off with a medium format camera - the one I'd taken to Central America with me. But it was obvious that I couldn't really photograph the buildings in the way that I wanted. And there were issues about colour film when it first came out: that it didn't have the resolution that we wanted. So that was one of the reasons why a lot of people went to 8 x 10 - I think initially motivated by the quality of the larger negative. When I moved to the View camera and started making pictures, I had to be pretty intentional. There was also discussion about the politics of photographing strangers. I thought if I had a View camera, if you didn't want me to take your picture you could certainly walk away before I could make an image. There was a kind of dance - a kind of a physical-ness to using the View camera on those streets. The View camera makes that happen, you have a dynamic relationship to the place and the people you photograph.

How so?

Using a tripod and View camera takes a few minutes to set up. You have your head covered with a black cloth, and then you take all that off and you put the film in and then you stand there and, okay, hold still, and you click (laughs). So what people often said about my work is it looked too loose to have been done with a View camera. But now we look back from the fluid way in which we photograph everything now - from cell phones and the like - and these pictures seem very formal. I used the View camera like I had been using a handheld camera. I don't tend to stage things at all. I'm not working from a predetermined idea of how things should be. I respond to what is.

South of Market was defined by bulky buildings on broad boulevards – there was no strong sense of place. North Beach had cafés, Chinatown's roofs had filigree of Chinese motif, and the Financial District was cold and windy with high-rises. I mean, places have identities, but South of Market was just where all the work got done - the print shops and car shops. It didn't have any personality to speak of and no one thought about it. Using the View Camera gave a sense of importance to this unnamed place.

Has the way the images been received change over time?

That is a really important point. The work garnered some support when I first made it because of its unique format and social commentary. I received two big grants to do the project. It was valued but not seen very much. Now the audience interacts with it as a way to travel back in time and imagine what the city was like before technology. Many newcomers are delighted to have these photographs of a neighbourhood that has changed dramatically and is now the centre of this new tech industry. But there was also another response that was very moving to me. I was at the exhibition [South of Market, de Young Museum, San Francisco 2015] and a Filipino woman came in and said: I can't believe you photographed my neighbourhood - nobody ever cared about it. She was so moved that somebody had spent time and acknowledged her home and that now these photographs were in the museum. I think our relationship to place is very important, and particularly now when there is the capacity to live totally ungrounded: in your computer, on the plane, from city to city.

People are talking about San Francisco becoming a vertical city.

Which is ironic, given the fact that it's on landfill and a fault line. But, hey, we haven't had a big quake for a while. We forget. But honestly we do need to go up, make taller buildings to house more people. That is happening east of Fremont Street now. Big expensive high-rise apartments are coming up everywhere in SoMa. The moratorium on building that was voted for in 1986, known as Proposition M, really slowed growth and has had a lot of unintended consequences now that there is such a demand to live and work in cities. But we need to use the airspace if we are to house everyone who wants to live here. If we don't expand the city will have a monoculture of very wealthy people and workers will have to commute from the outlying areas. I think in fact that is already the case.

Janet Delaney, Office workers on lunch break near the site of the new convention centre, 4th at Minna Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Office workers on lunch break near the site of the new convention centre, 4th at Minna Street. Courtesy of the artist.

The titles of the photographs provide just enough information about the individuals to become very intriguing.

Yes. I wanted the photographs to be specifically identified with the addresses, and I wanted the subjects names in there. I wanted the photographs to be grounded in fact. I spent a great deal of time looking at historical archives of images of cities so I appreciated those fact and that this work would hold that purpose along side the goal of social political art work.

This project is not about me. I think that's really important. It's a document. I made this document; then I put it away. Then I had a family. I did a lot of work that was more about me, and my internal struggles. But I always knew I wanted to bring this work back into the world again. People would ask, 'When are you going to do it' - I'd say I'm busy, I'm raising children, I'm taking care of aged parents and teaching full-time. When the opportunity to do the book [Janet Delaney, South of Market, Mack 2013] came up, I realised that I was just going to make this thing finally have the life it needed. So I have thrown myself back into it since 2011.

So you didn't show South of Market until 2011?

I had one initial show with Connie Hatch. We received a National Endowment for the Arts Survey grant in 1979 and we showed our projects in 1981. She did a body of work and I did one; we didn't work together. Our work was very different, but we collaborated all the time with conversations. She really helped me shape my ideas. I also read and heard Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler speak a few times - they were primary in my understanding of a new document that involved the participation of the people being photographed.

Where was it shown?

At San Francisco Camerawork in 1982, which was located on 12th Street in the South of Market at the time. This was an important alternative gallery space; in fact it still exists. Many neighbourhood people came to the opening, it was the first time attending an art show for many of them. In 1982 I also showed it at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, which was actually a hotbed of social document at that moment. People there immediately understood that I was addressing gentrification because it was happening everywhere. I realised there were many places that would respond - it didn't just have to be San Francisco. I really wanted the work to have political impact. In San Francisco I was working with various organisations, but they didn't really know what to do with art and I didn't really understand politics. I could see that city politics were really complicated and I was just getting frustrated. Finally I had to move out of South of Market. I needed a new apartment and I couldn't afford to live there anymore so I moved to the Mission.

Over what period were the South of Market photographs taken?

The first pictures were made in 1978. Most of my negatives are dated '80 - '82. When I got out of graduate school I started teaching full-time. In 1984 somebody came to my studio in the Mission and said they had a revolution and everybody's going to Nicaragua and you ought to return. And I'm like, all right, I'm going, I'm out of here, I'm going to where we can actually do political art. So I went full-tilt to become very active in the Sandinista support system. I photographed with Oxfam – who set me up with one particular family. I worked with them in much the same way I'd photographed my father, the salesman and my neighbours in South of Market. I got another NEA grant to do this. I loved the fact that I had to sign a loyalty oath.

Loyalty oath?

Yes. At that point the idea of funding artists was starting to get very suspect. Reagan had come in - you can't dismiss the impact of Ronald Reagan on all aspects of our lives. Remember he was supporting the opposition to the Nicaraguan Revolution through covert deals with Iran. So when I received the grant I had to swear I was loyal to my country. We were just entering into a very conservative era.

I lived with the Montano family while I was working for Oxfam. I spoke Spanish well enough and thought I would make a record of this one family's life and their relationship to the revolution. The house was so full of people and it was so chaotic that I never really felt like I was able to get the audio that I needed. The grandmother, the night before I left, sat down and wrote her story: My Life Before and After the Liberation of Nicaragua Libre. It was so moving; it was like she just poured it out for me. I translated it and recorded an older Latina reading her testimonial. Then I made a two-projector slide show to go with her story. I exhibited this piece in a show titled the Situated Image with Tony Labat and Gary Hill and a few others, in a gallery at the University of California, San Diego in 1987.

I can see the work's not about you, yet you are such an instrument within it. There is something about your relationship with the people that you're photographing that is integral to the work.

Right. I really love meeting new people. My father the salesman said he never met a stranger. I think people responded to my generally positive intent.

You obviously came to know quite a lot about people's lives. Is that something that you would do in preparation for the photo, or did this happen in different ways?

It would happen in different ways. For example I got to know Bobby Washington from the South of Market project because she was my neighbour. I would just pop over to visit some times and we'd talk on the street. I grew up in a quiet neighbourhood of Los Angeles, Compton. The neighbours got to know each other very well, because they'd all moved in at the same time and had children together. Everybody on the street would go camping together – the kids would have sleepovers and it was a really tight-knit community. The idea that you would know everyone on the street was just how I was raised. This was the same way Bobby had grown up on Langton Street. We are about the same age. But when I first came to South of Market I was held up at knifepoint. I lost all my equipment. So I thought I really do need to know my neighbours, because I need to know who's a stranger and who's local. It was outwardly a tough neighbourhood. As one neighbour said, 'My friends think I should be armed to the teeth just to live here.'

Janet Delaney, Mercantile Building, Mission and 3rd Streets. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Mercantile Building, Mission and 3rd Streets. Courtesy of the artist.

You said that when you took the photographs of Breen's Bar you were quite nervous about being there.

The neighbourhood was very much one of poverty - people were drunk on the street. I'm much more comfortable with that now (unfortunately), but at the time I was still getting my streetwise nature about me. I was just looking at that picture recently and you can see Breen's is almost boarded-up - it was just about ready to be torn down. In front of the building there are these office people scurrying by in their high heels and pale blue suits, with wide lapels. In the 1970s the financial district built a lot of their outbuildings, so to speak - where they had their secretary pools - in the South of Market, because the land was cheaper. Then they could have their higher-end administration North of Market. So there was always this odd flow of the suits and tight skirts going back and forth across Market Street. Stepping around people drunk and asleep on the street.

There's that remarkable picture of the Mercantile building on 3rd and Mission, where Tom Marioni first located the Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA) - and around it there is just nothing.

Empty parking lots. That was the way the city looked for ten years before they started to build the convention centre. Litigation was brought against the Redevelopment Department to demand replacement housing for the seniors who had been displaced. Most of them never made it to the new housing - it took so long, because the developers fought against the replacement housing. This struggle ultimately changed the way redevelopment happened. I can't say now that we shouldn't have built the Moscone Centre - it's the way the city grew and developed, and it serves an amazing function. The city was a working-class city before the Moscone Centre came, but the Moscone Centre follows the closing of the port and the fact that we no longer had that kind of working class industry. The ships moved over to Oakland because the San Francisco wharf wasn't built for container cargo. And at this same time a lot of the factory jobs were leaving and either going offshore or to other parts of the country - or even just the East Bay. The city was changing. Now, the idea of the city, the function of the city - is Information Technology: that's the industry we're in. Also finance, tourism and biotech. These are all industries that have high salaried jobs.

Back to the empty parking lots. So they wanted to put hotels and office buildings up all around the new convention centre but the neighbourhood was poor and still had a number of bars and alcoholics on the streets. They used the term, cordon sanitaire. To describe what they needed to create around the new convention centre so when they built the Moscone Centre they made sure that the area all around it was also available for development. That's how they brought in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which opened in '95 - which is a fantastic thing. But if you look at the way the Moscone Centre was built, it's like a fortress on three sides - you really wouldn't want to walk on the streets that around it when it was first there.

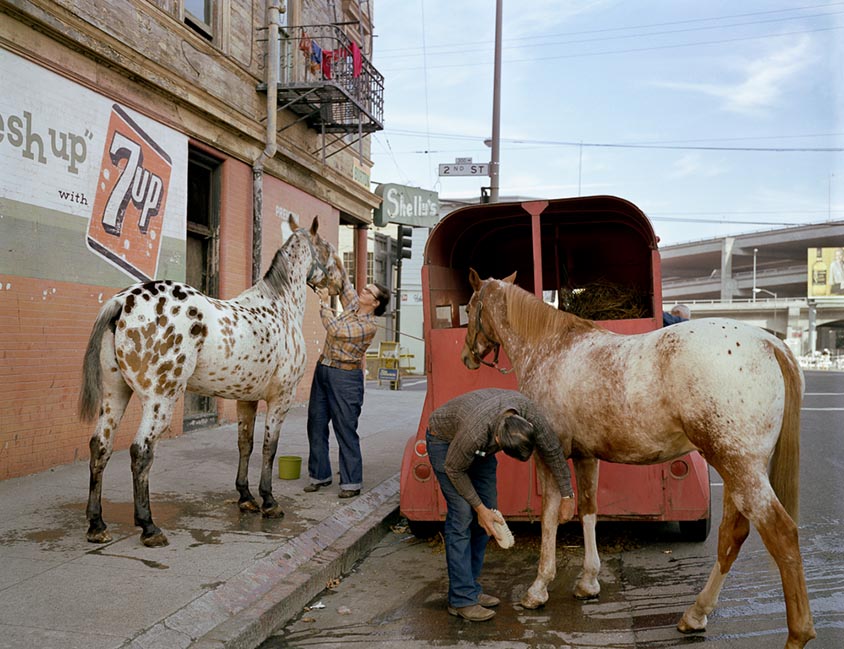

Janet Delaney, Skip Wheeler and his wife groom their horses after Veteran's Day Parade, Folsom at 2nd Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Skip Wheeler and his wife groom their horses after Veteran's Day Parade, Folsom at 2nd Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Even now, from the street the Moscone Centre architecture makes you feel pushed away.

Yes because its original intention was to buffer you from all the poverty that surrounded it. It's an interesting and uneasy relationship now. 6th street is where most of the low-income housing is. There are a number of services for the indigent. Most of my work now is about the super-rich and the super-poor in South of Market. I'm just getting started with that project now.

Were there horses in South of Market?

(laughs) Well, you know, it was a parade. I went with my View camera to the Veterans Day Parade. I photographed a few marching bands and the like. Then I was looking around the periphery and I was just taken by that little scene. They were all just in the process of putting their horses away, I think, after the parade. It's interesting in the sense that everything in the photo is an illusion – I like the idea of a unicorn in front of what is now an internet switching hub. The big silver building behind the horses is owned by ATT, a telecommunications company.

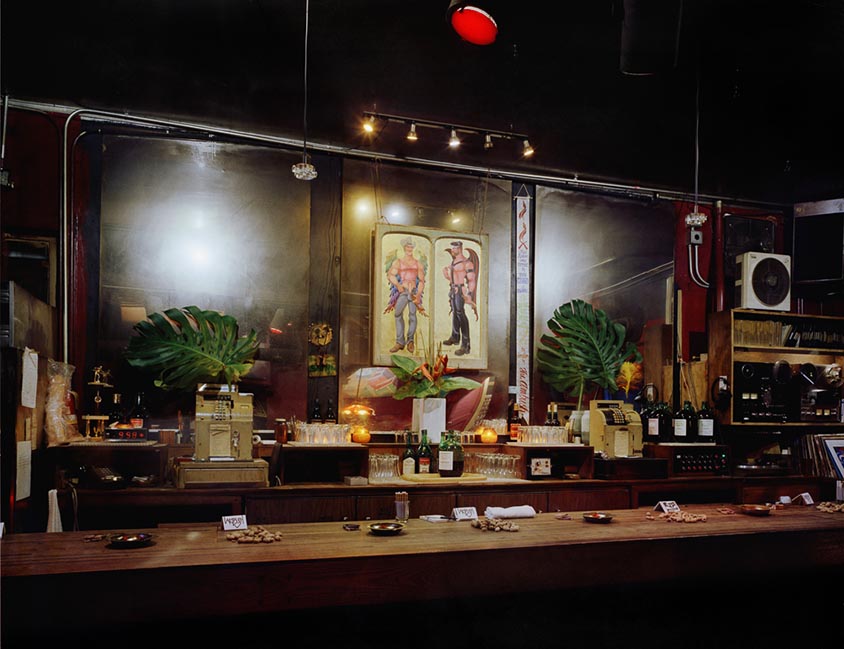

Janet Delaney, Ambush Bar, 1051 Harrison Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Ambush Bar, 1051 Harrison Street. Courtesy of the artist.

The other thing we haven't really even talked about is the gay community in South of Market. It was a huge part of the neighbourhood culture. And I don't know if I mentioned to you before, but if you want to read the history of the South of Market, the best place to go is the Folsom Street Fair website.

Waves of people come to San Francisco – and with each wave, it's a small enough city that it gets taken over. In the 1950s we became the Beat poet neighbourhood. You know, North Beach - that was sort of just coursing through the culture. Then in the late 1960s, the Summer of Love and the Age of Aquarius arrive - and you had this amazing sort of visionary, slightly drug-induced state of mind. Then I'm standing there on the corner of Castro and Market one day and I'm looking around and it's not the same: who are all these new people? There are all these handsome young men and they're not looking at me (laughs) and I'm like - what happened? I realised then that the predominant culture is the gay culture. When I came of age in my early 20s, my friends and I realized we didn't have anyone to go out with. It was just so absolute. I went for a couple of years without a date. I swear to God I'm not kidding. When I first moved into San Francisco I moved near Polk Street and I worked in a restaurant that was owned by two gay men. We had the first vegetarian restaurant - it was very fancy, and I was the baker at the time. I walked to work at 2am - it was mostly men on the street, young men, pimping themselves to older men who were cruising in from the suburbs. The leather scene got established in the South of Market in the late 1950s, early 1960s I think. This area became interesting to the gay community because you really could do whatever you wanted there. There wasn't a predominant culture. The Filipino and African American and Greek communities were all there, but a lot of people would arrive in South of Market, get a job and then keep going, moving on to better neighbourhoods, because it wasn't great living there among the auto shops and print shops. The gay community could live there - they didn't need schools and parks for kids, because at that point gay men were not having children. I think they probably took over the working-class bars and turned them into gay bars, I think they were probably the dives of the past where the guys who worked the nightshift would go or what-have-you. The artists took over some abandoned warehouses and the gay community made others into bathhouses, where sex was easy. Gay men started to buy up a lot of the three story apartment houses that were tucked in between the light industrial workshops. My landlords were gay. They bought our three-unit apartment house right after we moved in, in 1978. They came from Saint Paul [Minnesota]. There's an interview in the book: Tom Whiting and Ted Hack. In my interview, he says: 'I'm not going any farther west, I can't go any farther, I came here because it's a sense of freedom. I can be who I want to be in San Francisco.' It was a really important part of how culture in the city played out.

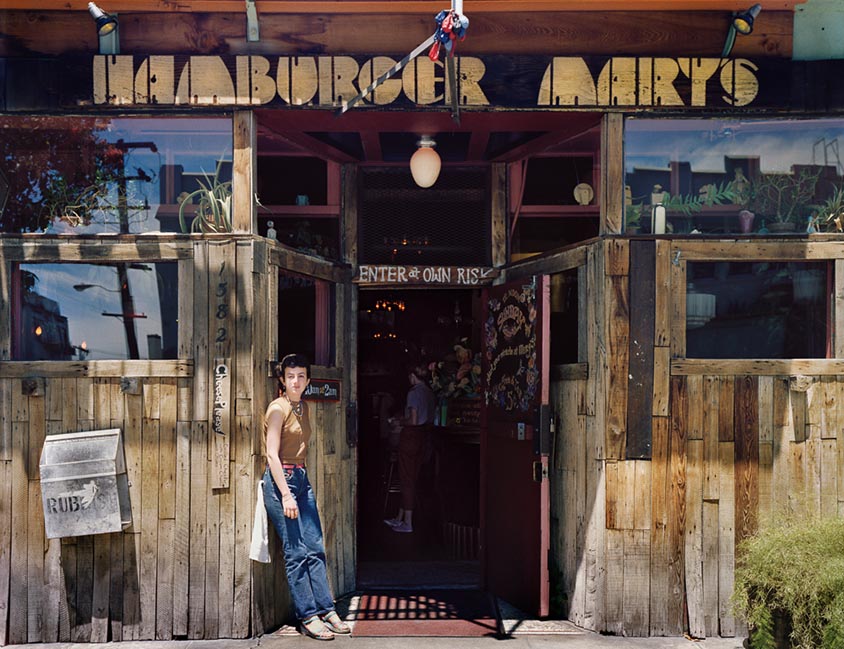

The photograph of Hamburger Mary's - we all went there after drinking, we'd go for brunch in the morning, they had great eggs. It was a gay restaurant where a lot of straight people went. A lot of straight people would go to the gay bars also, because there really wasn't any other bar to go to. And also it was more fun, better disco! So there was really, I think, a lot of overlapping at that point. And then the AIDS epidemic came through and that was the end of a lot of it. So the gay community played a big role in the culture of South of Market.

Janet Delaney, Hamburger Mary's, Folsom at 10th Street. Courtesy of the artist.

Janet Delaney, Hamburger Mary's, Folsom at 10th Street. Courtesy of the artist.

When did you decide to go back start to shoot in South of Market again?

People had said I should photograph again in South of Market. After I put together a book dummy of the South of Market project - and when I actually had the contract with Mack to do the book, I thought that I needed to look at what's there now to understand better what I'd produced.

So you're photographing the super-rich and the super-poor.

Well, I photograph what's in South of Market and that's pretty much what I'm finding [SoMA Now (ongoing)]. I'm open to photographing other things; it's just that I have been concentrating on photographing the new buildings coming up, because it won't always be happening. When I was photographing South of Market in 1980, we did not have people sleeping on the streets everywhere like we do now. Then, I hardly saw it at all. I know there was poverty, but it was just at the moment when services were being withdrawn and government aid was being pared down. Ronald Reagan had been our governor before he became President, so California experienced the withdrawal of services and the idea of small government sooner than the rest of the country did.

Homeless people sleeping on the street seem such a profound aspect of the city.

It really is. But now there is an amazing network of social services. I wont apologize for the situation but it is important to note how the city is responding. There was a recent article in San Francisco Magazine by Gary Kamiya about all the things the city is doing - 'The Outsiders'. He compared it to other cities and said San Francisco has this reputation because you can see the poor - other cities have displaced them in ways that they're just not as apparent. In the last three weeks or so I have been photographing for an organisation called Homeless Prenatal, and so I have been going into the hotels in the Tenderloin and out to Bayview. There was a young pregnant woman who was living in Golden Gate Park. Social services located her and brought her to HPP. I photographed two heroin addicts that have come clean and have a baby - and he's going back to school for carpentry. And they all have this amazing network of support that exists here. There is a huge, liberal and very caring community here. And yet at the same time it seems like we're not doing enough. You see one person, it seems too many - and it is. So it's an endemic and problematic phenomenon. It's always one of those topics that people are very sensitive about photographing: like, it's exploitative and sensational. So I said, what - if I don't take pictures it makes it go away? No, we have to look at it.

Janet Delaney's website is available at http://www.janetdelaney.com.