Doug Hall

Interviewed by Nick Kaye, San Francisco 25 October 2012

Follow the links for discussion of: Great Moments (1971) | The Eternal Frame (1973) | Walking Mission Street (1972) | Thirty-two Feet Per Second Per Second (1972) | The Amarillo News Tapes (1985) | Game of the Week (1977) | Chapters From the Life of: A Soap Opera (1980) | Songs of the 80s (1981) | Machinery for the Re-education of a Delinquent Dictator (1983) | The Victims' Regret (1984) | The Terrible Uncertainty of the Thing Described (1987) | People in Buildings (1989) | Storm and Stress (1986) | Gene Autry Rock, Alabama Hills, California (2002) | Monument Valley (2008) | Glacier Point (2004), Wall Street (2004) | People in the City (series, 2010) | Market Street, San Francisco, 6-15-2010 (2010) | Chrysopylae (2012)

Q: I was interested firstly in how you'd arrived at working with T. R. Uthco in the medium of performance.

DH: I have to go back pretty far to the early 1960s in Cambridge, Massachusetts where Jody Procter and I were roommates in college. We were both profoundly affected by the social and political climate of the time. There was a combination of influences. JFK was assassinated my sophomore year; the conflict in Vietnam was escalating; the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing; And there was the incursion of drugs into what had been a very pristine, privileged, academic environment. I found myself in the midst of this turmoil and attracted to the more radical critiques from academia as well as the streets. And I was looking for a way to express myself within this. To have a voice. I think Jody was too. For him it was more through writing. For me it was through art. An art based on some sort of action. On some sort of irreverent behavior. I suppose we thought at the time that in order for art to be relevant there had to be risk involved, physical or mental risk involved. But I make it sound like I had this all figured out back then and I surely didn't. I was groping for sure. Probably still am.

Although I was an Anthropology major, I took as many art classes as I could. Because of the university's distrust of art practice, these were mainly design classes offered through the architecture program. I took Robert Gardner's film class. I applied to both UCLA film school and the Rinehart School of Sculpture at the Maryland Institute of Art, and was accepted into both. I went to Rinehart where I started to learn how to make things. I don't think I knew what I wanted to do there. Probably just stay out of the draft for a couple of years. I was pretty sure I wasn't interested in making sculpture, traditional sculpture, although I am not sure I knew enough then to make that judgment. The school accepted me into a 3-year program as I kind of experiment. I started making things. I tested materials. I made little films. I did some performances. In some ways it was a continuation of things I had been doing in college where I had done performances – more like pranks or actions in the streets with political overtones. I had been in a couple of student films and had minor parts in college plays. Jody and I had started fooling with the image of JFK. He even wrote a speech–actually a speech about making a speech–which I delivered in a Kennedy accent as my acceptance speech into The Signet Society, a university literary society. I suppose this is the beginnings of the Artist-President, which culminates in our assassination re-enactment, The Eternal Frame (1973).

And then in the summer between my first and second years of graduate school, I met Diane Andrews in Maine at the Showhegan School. She was on her way to Boston University to study with Walter Murch, a wonderful painter and the father of the well known filmmaker of the same name. We became involved. Diane was from Dallas via Sophie Newcomb College, the women's side of Tulane University where she was an art major and did a lot of work in the theatre. She had an adventurous spirit and we hit it off immediately. Enough so that we took the inexplicable risk of getting married that winter. She transferred to the Hoffberger School at the Maryland Institute. We finished grad school together and in the late spring of 1969 moved to San Francisco. Jody, now married to my younger sister, was already there, and we decided to form some sort of collective between the three of us. Our motivation was utopian – that somehow art could change the world. That art and life could merge. Should merge. We were hippies. We called ourselves The Land Truth Circus.

Q: And one of the earliest performances that you did referenced Gilbert & George.

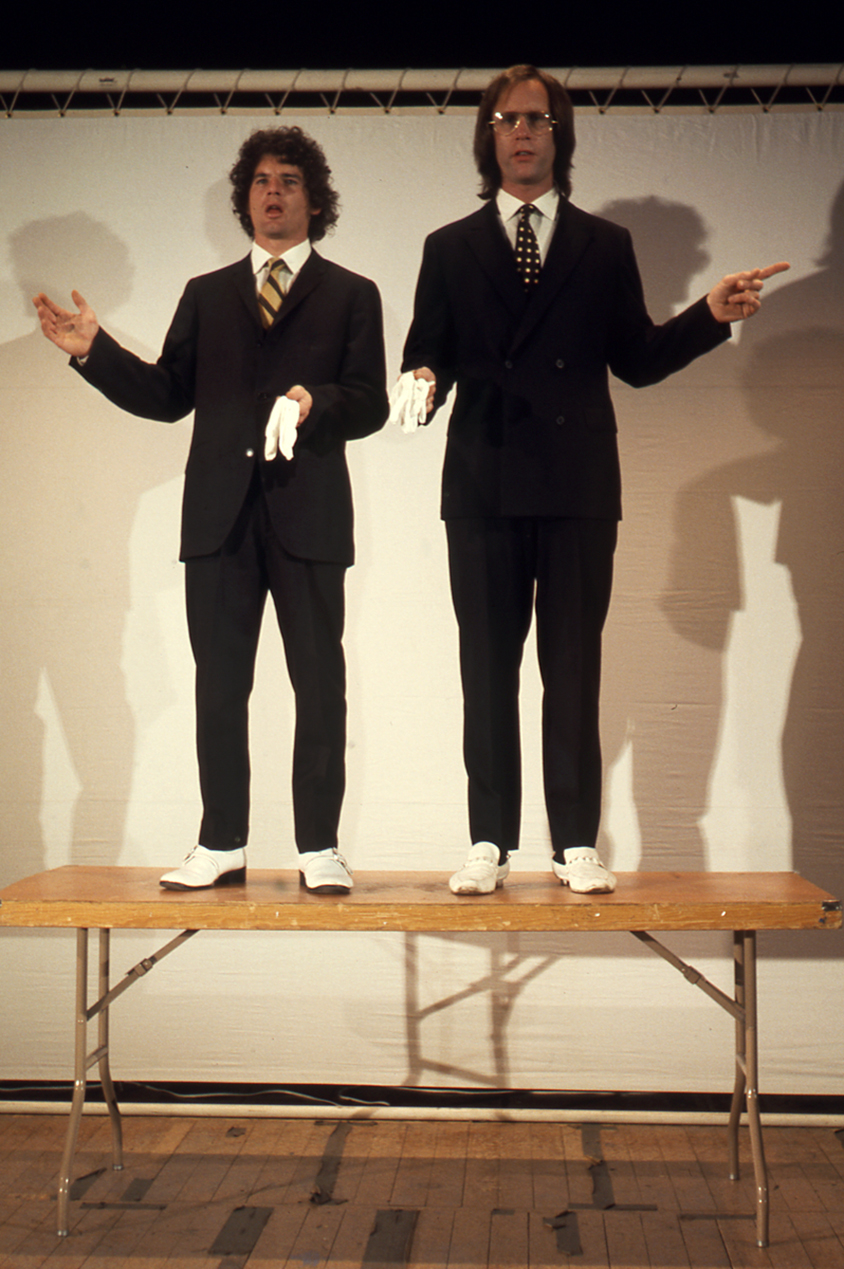

T. R. Uthco, A Trick My Grandmother Taught Me from Great Moments. Live performance. Photo: Diane Andrews Hall. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

DH: Right. We did a piece called Great Moments (1971). By that time we were a little more sophisticated and had changed our name to, T. R. Uthco. It was a staged performance and it had, I think, eight separate episodes or "acts". Jody and I were the main performers. Diane was involved in staging and directing. A lot of the content dealt with illusions or deceptions created by media. For example, one of the scenes was a piece called Standing Man, which was based on a series of slides that Jody had found in a dumpster behind one of the media labs in San Francisco. The slides depicted two men in suits photographed individually against a neutral background with the right hand extended as if about to shake hands with an invisible person. There were other images of the two men: closeups of their faces staring off into space, etc. Very strange. Very Uthco as we used to say. We took slides of ourselves imitating the gestures as closely as we could with our limited skills and resources. In the performance we mixed their slides with our imitations, and at times stepped into slides of them so that our identities sort of merged. I think the sequence ended with Jody standing there in a white shirt with a white tie, having a film projected on him of himself in a blue shirt tying a tie so that the projection and the live performance overlapped, falling in and out of synch with one another. And then there was Gilbert & George, I mean it was sort of like doing a ...

T. R. Uthco, Underneath the Arches (after Gilbert and George) from Great Moments. Live performance with pre-recorded sound. Photo: Diane Andrews Hall. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

Q: A cover -

DH: Yes, exactly. One of the acts in Great Moments was our rendition of Underneath the Arches. We stood on a table, much as Gilbert & George had done, and lip synched the British Depression era song, Underneath the Arches. Although in their performance I think they actually sang the song.

Q: I'm interested, because doing a cover of Underneath the Arches seems to reflect a theme of your work inhabiting other things.

DH: Yes, absolutely.

Q: And I'm also interested in this question of risk, because some of the things that you did were actually physically risky.

DH: Yeah, I mean it's interesting. In a way it's almost embarrassing for me to talk about it now, because I have such a different view of things, and the needs that making art fulfilled for me have changed. But I do think that at the time we imagined ourselves functioning subversively. We saw mainstream art, perhaps all mainstream culture, as being compromised by its association with all of the things we were questioning – embodied I suppose in what we saw as America's imperialist audacity. Art seemed to have acquiesced and turned its back on its role as critic. I guess we saw ourselves affiliated with those artists who were reviving oppositional strategies. Art could ask questions, drop flies into the ointment, become the itch you couldn't reach. We had the notion, shared by a lot of our peers, that there was a way of inverting the calculus so that art could be productive and could address things that mattered. That it could be political. We were never interested in, nor practiced, direct political art. We felt that the politics of art functioned differently. Not through head on attack but by subverting meaning. Perhaps by working through allegory or analogy. Looking back at this time, I suppose we thought that if one is to gesture into the flow of spectacularized images, a certain degree of risk had to be involved for the action to rise above the surrounding roar. I think we felt that the price for taking an oppositional stand against various systems of power had to be paid by risking the body and the psyche - and that somehow this legitimised what otherwise was a very self-indulgent kind of behaviour. And if you're motivated by a delusion or politics (laughs) – or if it's delusional or if it was delusional – then you need some sort of rationale, a way of behaving, within this that brings personal sustenance, because we certainly weren't making much money from it. Nor were we winning friends in high places.

Q: But one of the interesting things to me is the particular way in which you do that, because, for example, if you compare it with Chris Burden, say, there's a very interesting film of Burden doing a performance at MOCA, where he essentially takes his jacket off, sets fire to it and then jumps on the jacket and puts the flames out [Fire Roll (1973)]. Which is - in a way - a very straightforward proposition around risk. When you're taking physical risks with T.R. Uthco, or putting yourself in a situation like walking down Mission Street, it seems constantly feathered into this question of media or mediation.

DH: Right. It's about how images circulate (or how meaning circulates within these images) and where we find ourselves within that circulation. For example, our re-enactment of the Kennedy assassination, The Eternal Frame (1973), which is based on an actual event, but is a ruthless and some would say irresponsible distortion of history. But what it really is is a form of appropriation, an avant garde strategy that reaches back at least to the beginning of the last century. Through appropriation we temporarily occupy the bodies of the participants in the trauma and we do this within Dealey Plaza, the actual site of the tragedy and in the act we collapse time and distance. We remould the event, we press it against our own bodies and psyches, and we claim it for ourselves. Not only for ourselves but by analogy for those who might view the resulting video. And by claiming it we recognise that we are not, in fact, totally at the mercy of the culture industry or whatever one might call it, that we do have agency. This I believe is the conceit at any rate.

Q: The piece, Walking Mission Street (1972), what was that comprised of?

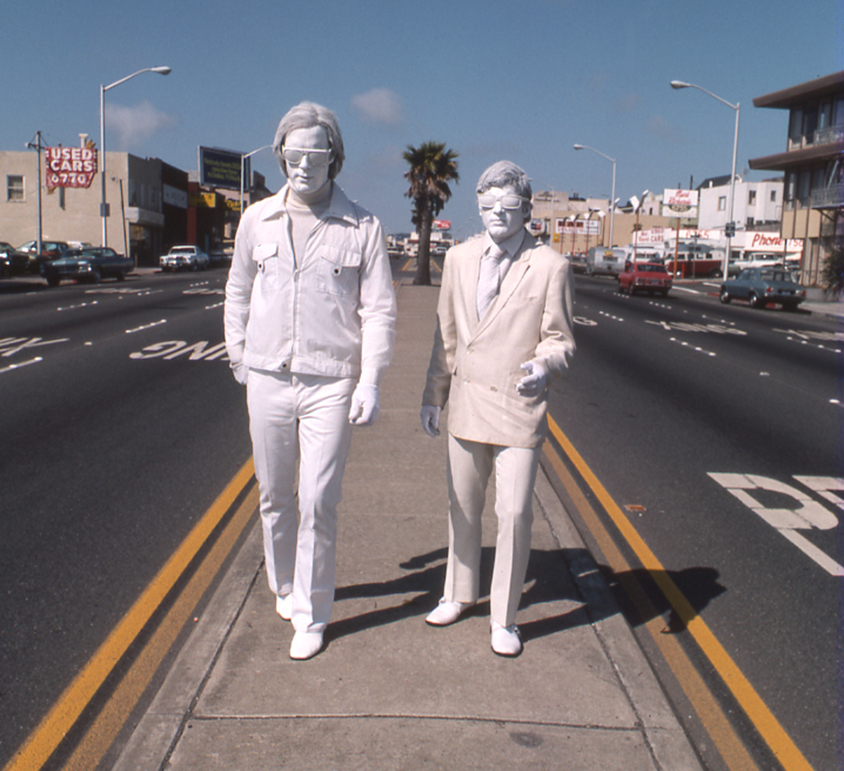

T. R. Uthco, Walking Mission Street, Live performance. Photo: Diane Andrews Hall. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

DH: We started out on Mission Street, I guess, in Daly City, with the intention of walking its entire length to the Embarcadero, although I don't think we actually made it that far. And I can't remember the exact rationale other than to say it was an intervention into the urban landscape. Those figures–the white men–originated with a piece called, Thirty-two Feet Per Second Per Second (1972), an eight hour performance in which Jody and I sat in chairs bolted to the façade above the third floor windows of La Mamelle, an art space in San Francisco. We were miced and there were two video cameras mounted so that we could be viewed and heard in the gallery. We would use these kinds of difficult physical or psychological situations as ways to help us generate content for our double monologues.

T.R. Uthco, 32 Feet Per Second Per Second. Live performance. Photo: Kit Sibert. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

In the Mission Street piece, we thought of these as white guys walking through the city. And it was very much about making an image. It wasn't much more profound than that.

Q: Did you get responses to that?

DH: Yeah, we got a lot of, 'Hey, white guys!' - nothing very aggressive actually. And sometimes we were alone and then Diane came and took photographs. We never spoke. We just walked through the city. It was an intervention into the everydayness of urban life. Our presence infected the space as we moved through it. Thinking about it in retrospect, there was this notion that the spaces we inhabit dictate the kinds of behaviors permissible within them and that our gestures into those spaces were a way of reclaiming them or at least treading on the rules that governed them. It was also a pretty funny image.

Q: It's interesting that in subsequent works you occupy, if you like, the mechanisms behind the media - when you were resident artist with a news corporation, for example.

DH: You're referring to the project we did at KVII Television in Amarillo that resulted in the video, The Amarillo New Tapes (1985), a collaboration between Chip Lord (a founding member of Ant Farm), Jody Procter, and myself.Actually I conceived of a trilogy of so-called "artist-in-residencies," two of which were completed. The three areas were to be a professional sports, The White House, and a small market television news station. The first, the professional sports residency had me interacting with the 1972 San Francisco Giants baseball team and resulted in the video, Game of the Week (1977). In 1977, I came very close to getting into the Carter Whitehouse because of connections we had with Joan Mondale, but at the last minute a scandal erupted around Bert Lance, an important member of Carter's administration, which made access impossible. The residency at a television station was easy because of our previous association with Stanley Marsh, who owned KVII Television. Ant Farm's Cadillac Ranch was commissioned by Stanley and located on his land. Also, Marsh was intimately involved in our Kennedy assassination re-enactment in Dallas.

At KVII each of us took on roles. Jody became the sports guy, I became one of the news anchor guys, and Chip became the weather guy. It is interesting how each of us naturally gravitated toward our particular roles. We arrived without any clear idea of what we were going to do. We only knew that we were interested in the staging of news and felt reasonably confident that we could accomplish something while we were there. Then an incredible tornado roared through Wichita Falls, which changed everything. Suddenly we were in a real news story (laughs) for better or worse. I think it was interesting because our fanciful, somewhat intellectualized deconstruction of the news was suddenly interrupted by a catastrophic and highly newsworthy event and we found ourselves in helicopters or in the KVII Pro News van, rushing to the scenes of the disaster. We were no longer distant observers but were fully embedded accomplices, assisting the reporters as they covered the story.

Q: So you were assimilated?

DH: Yes. We ended up helping them. It's like the newsmen being dropped in with the American troops in Iraq or something - suddenly you are participating.

Q: And was it this engagement with video that moved you away from live performance?

DH: Certain things happened that made performance no longer productive for me. After T.R. Uthco split up I did a few performances. One that stands out is 7 Chapters From the Life of: A Soap Opera (1980), a series of seven performances done over seven nights as a sequence of tableaux or chapters. That was, I think, in December 1979. Into the early 80s I did a few performances under the title, Songs of the 80s (1981). Several of the episodes in my video of the same title were made for those performances. And then it no longer was working for me - the politics had changed. My heart was no longer in it. I needed some distance. Critical distance. It's what Walter Benjamin in his essay, Surrealism, identified as "profane illumination." While he says it is important to become involved in the disorienting frenzy of the time. To become intoxicated as the Surrealists surely were and as were many in my generation, it is also necessary to find ways of creating some distance so that one isn't entirely consumed. And as a performer I found it impossible to get that distance. I couldn't critique myself. I couldn't see what I was doing, and I felt like what I was doing was something that I was no longer really committed to. And it took a while to figure out how to operate outside of that.

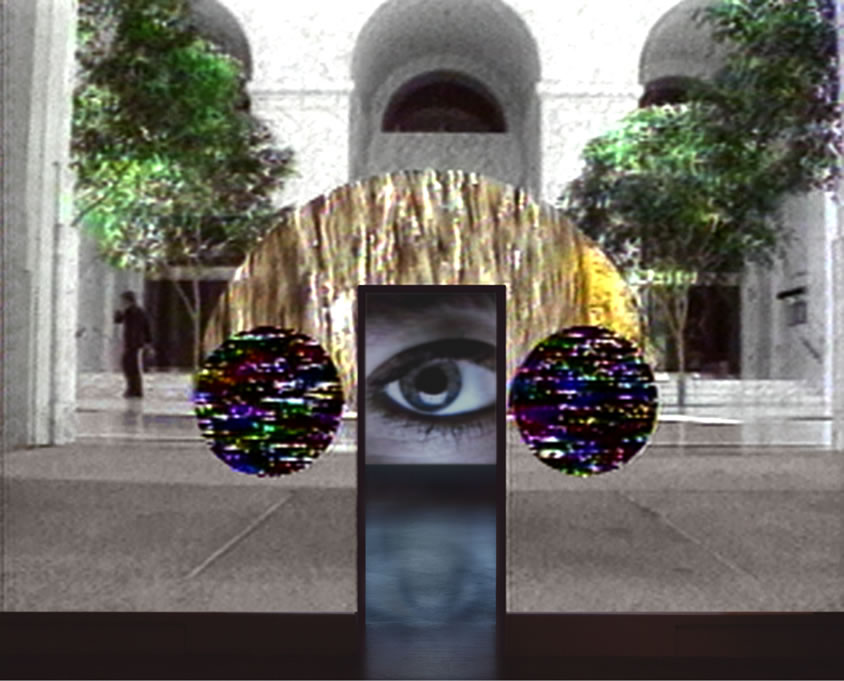

Video installation, which I saw as somewhere between live action and representation, became a way forward. Most of these were done in the '80s into the mid '90s. There are four or five, which I still think of as significant today. In the earlier works like Machinery for the Re-education of a Delinquent Dictator (1983) and The Victims' Regret (1984), I perform for the video. They have a lot of things in common with what I had been doing in performance and in the video, Songs of the 80s. They are psychological and expressive. And then the installations began to shift or at least the position of my body within them began to shift: a significant move from before the lens to behind it. By the time we get to pieces like The Terrible Uncertainty of the Thing Described (1987) I have completed the move to behind the camera: I'm observing space, observing myself in space, but allowing the space, the people, and the circumstances to unfold as a way to address issues about media, architecture and the body. These are certainly the subject matter of my two-channel installation, People in Buildings from 1989. This is also when I began using large format photography in a serious way to make photographs of several of the corridors that appear in the video. At the time it seemed necessary to strip the people from the spaces, although – and this was also important to me – the corridors are filled with people moving through them but because of the very long exposures they aren't visible. I thought at the time that I was enacting the photographic equivalent of the neutron bomb – only the people are eradicated and what's left are the structures they inhabit. The psychology of space and how our bodies find themselves within them were of real interest to me – and still are.

Doug Hall, People In Buildings, installation view. 2 channel projected video installation. Photo: Ben Blackwell. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

Q: You have described your early work as a kind of making space within a use of images. It seems to me that your work precedes what became something of an idea in the '80s, particularly about one thing – practice – inhabiting and disrupting another. Then, at the point this became a predominant style you stepped out of it, but carried an element of this forward into your photography. One of the things that I find fascinating about your photography is the way that there is this sense of almost a pause, almost like a space in which something is going to happen but you're left at that moment of possibility.

DH: It's so curious and encouraging that you would notice that. It's sort of the psychology, the kind of unstated psychology of space, or at least how I find myself within those spaces.

Q: To me there is a sense in photographic series such as Anonymous Buildings (1989-91) that there is an evacuation of space that leaves it shadowed by some kind of presence, which is felt but imperceptible.

DH: Yeah. I have done a lot of photographs of places where people gather. The settings are often architecturally determined: places where people come together with certain expectations or desires to be fulfilled. I see these spaces functioning like stage sets - as if experience is being staged for and by us. Part of the source of our alienation might have something to do with this sense that experience is being co-opted. And, in fact, we find ourselves in these uncanny relationships to architecture or built space, so we don't quite know what to do with our bodies or with our psyches. Benjamin writes about this a little bit in Art in The Age of Mechanical Reproducibility - that last section where he talks about how we move through space in a state of distraction. I think he's talking about our unconscious interactions with aspects of the built world. We find ourselves dressing up in, or wearing, the spaces that we inhabit and move through.

Q: The uncanny is also a kind of out-of-body experience, isn't it, where you recognise your presence in something else.

DH: Yes.

Q: It seems to me that there's an element that flows through much of your work about recognition. So there will be something familiar in the image – and sometimes you seem to make it explicit – such as a landscape that refers to a Western scene or film set. At other times it seems instead as if the way your practice inhabits the media is to explore how perceptions of a natural scene are already inhabited or articulated by media. And that's an uncanny experience.

DH: I think it can be an uncanny experience and not an entirely unpleasant one either. I should add, going back to the early work, I bought into the Situationist notion that somehow we're constantly at the mercy of forces that are greater than ourselves and that we can never really establish our own subjectivity outside of this bombardment of data. And now I think quite differently. I think that actually we have a much more dynamic relationship to the flow of information that is coming at us and which we're involved in generating. We often find ourselves in states of alienation, conditions of out-of-body and mind weirdness, but rather than having these be like a bad trip (laughs) they are actually part of the experience. I think that ultimately they nurture our imaginations - they play with our notion of ourselves, and the world. They can exhilarate us.

Q: That's another important theme, isn't it - there is a thread running through your work around environment, place, nature and their relationship to the technology, in works like Storm and Stress (1986).

DH: Part of the thing that fascinates me about landscape is this notion that somehow landscape is benign and beautiful. I think it's as terrifying and as benign and beautiful as anything else - we bring so many things to our act of looking and being in the world. One of the things that I notice about immense urban and non-urban expanses is their voraciousness, this sense that they are devouring the space around me. And maybe that's related to the sublime, which is so often cited in discussions of my work. But I think the condition is more existential than that. I think it has to do with the dilemma of subjectivity and objectivity, with being both inside and outside, with recognising the self and at the same time not recognising the self: one's presence and one's absence simultaneously.

Q: The scale of your photography in the gallery seems a very important part of its effect. I am thinking of Gene Autry Rock, Alabama Hills, California (2002) - which seems really strangely familiar, also. It looks like a film set -

Doug Hall, Gene Autry Rock, Alabama Hills, California, Digital C-print 50" x 62.75", 2002. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

DH: Oh, it is a film set. It's an important location in a Gene Autry film. I think an ambush takes place there. There are two locations where most of the famous American Westerns were shot, including a lot of TV Westerns like Bonanaza. One is the Alabama Hills, which is where Gene Autry Rock was taken, and the other is Monument Valley. My photograph, Monument Valley (2008) the portrait of the Native American in feathered and sequined regalia, was shot there; on a butte overlooking the valley used in a John Wayne movie and also a scene from Back to the Future. These form the Ur-landscape for the American west of our imaginations.

Q: And how large is the image when it's exhibited?

DH: It's about 50 inches by 63 inches. It's pretty big. But going back to scale, just one thing: today everyone's making pictures that scale. I think that I was - at least in the United States - one of the earlier ones to do it. And because I came to photography out of performance and installation, I was much more interested in how we intersect images with our bodies, and I was not at all attracted to arrangements of small photographs on a wall organized by subject matter - like a book on the wall. I wanted something that was much more physical and much more experiential than that.

Q: And that seems to be lodged in the way that you're dealing with the individuals that you're photographing. It often appears in the image that they're engaged in some act of presentation to you.

Doug Hall, Monument Valley, Utah, Digital Pigment Print, 50" x 64", 2008. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

DH: That appears to be the case. I should tell you how the pictures with groups of people are made. The process is perhaps more cinematic than traditionally photographic. First I take a master or establishing shot of the location. The way I might if I were making a movie. Then over a period of time, often several hours, I somewhat surreptitiously (as surreptitiously as you can with a large format camera on a tripod) take pictures of individuals and groups of people as they come into the space. I may take 12 – 20 more photos of a scene. I scan all the negatives at very high resolution and then in my computer I restage the scene, placing the people where I want them. This allows me to create relationships between people that don't really exist, or, more particularly, it allows me to create relationships of people to the spaces that could very possibly not even have happened there. For example, there's a photograph I made of Union Station in Los Angeles, and the people you see in the photograph were actually standing outdoors in front of Grauman's Chinese Theater. The positions of their bodies and the way the light falls on them is appropriate to that space and not to the space in which I have relocated them. It makes them seem slightly awkward in their surroundings as if their bodies can't be entirely accounted for.

Q: That's so interesting, because there's a sort of dissonant relationship between the people, each other, and the place. It is tangible and yet it looks so natural.

DH: My approach to the diptychs is similar in that they too compress extended time while seeming to present momentary time. With the camera on a tripod I first take one side and then the other which gives me the left and right master shots. Then I take the photos of the people who I later insert into the two sides of the diptych. This process creates a gap between the left and right panels, which is both physical and temporal. Now there are 2 ways to approach the gap that now exists between the two. One is to obscure the fact of the temporal break while perpetuating the illusion of instantaneous time. I can do this is by having a person straddle the gap. This is what I did in Glacier Point (2004), for example. By the way if you look at all closely at that photo you will notice that the shadows of the people fall in different directions and that of course is because they were photographed at different times of day. In any case the figure obscures the temporal shift but there are hints of the deception.

The second way to approach the gap is to accentuate it, to recognize it, which is exactly what I have done in Wall Street (2004). Here the two sides are printed on one large piece of paper with the thin white line of the paper separating them. No figure bridges the gap but rather the figures seem to fall into that gap, which I see as a void, a vector. For me this picture is so much about that gap and the decisions I made about how to deal with it.

I think it's in Sartre's Being and Nothingness, where he describes an instance when a person is standing alone in a park. Solitary, he is all subject, confident as he surveys his surrounding. But his subjectivity collapses as soon as another person enters. Now he is no longer the sole master of the scene but is object to another. Otherness has entered, and the boundaries separating subjectivity and objectivity have become fragile and permeable. Sartre says something amazing here. He says (and I hope I'm not distorting it too much) that it is as if a drain hole appears in his reality through which all equilibrium rushes out. And somehow in my interior monologue about what I'm doing, that gap in pictures like Wall Street fulfils a similar kind of function. For me it's like the suggestion of oblivion created by the converging lines of perspective in X-Corridor or some of the photos I did of desert highways. The dark hole at the end of time.

Q: That's really interesting. There is also this notion when you're dealing with a single individual, that you see some act of presentation. I'm thinking, for example, of the more recent series you have done, where you've taken photographs of individuals in Haight-Ashbury or on Market Street in San Francisco, as part of the People in the City series (2010) where the person being in that specific place seems to be a very important element in the photograph - and they seem to some degree quite self-conscious. I'm interested in what that encounter is.

Doug Hall, Market Street, San Francisco, June 15, 2010, Digital Pigment Print, 36" x 32", 2010. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

DH: These were very difficult for me to do and I am still not sure what I think of them. Working with an assistant, we had to arrest people's movement, had to reach into the flow of humanity and somewhat arbitrarily place individuals in front of the camera. And this all had to happen very quickly and efficiently. I was after a kind of awkwardness or indeterminancy. The precariousness of bodies as they move through urban space. In the exchange that takes place between me and the subject through the camera there is, I think, a unique oscillation between trust and mistrust. My hope is that what you see in these portraits is this awkward interruption of motion.

Q: It looks as though they want to be photographed, but they're still in the process of negotiating with you what it is, and so they're negotiating with you as a viewer over what you are seeing.

DH: I'm pleased if you see that in them.

Q: The other thing is that the title of these images is the place and time of its making. For example, Market Street, San Francisco, 6-15-2010 (2010).

DH: It's interesting. I change the titles all the time. Sometimes I name the people; sometimes I call them a man or a woman. I certainly want to locate them in the city.

Q: You could be capturing people in the flow of the everyday, but somehow the photographs are puncturing that and so making some kind of space that is interrupted, suspended.

DH: Right. It's momentarily suspended space. It's as if space is pulled aside and asked to stay put for a photograph. This is so different from the sense of immediacy that one gets from a Winogrand photo for example.

Q: So in my mind there's the question of time as well in your work, and a lot of that's been implied in what you've been talking about. But it does seem almost like your early work is performance and explicitly time-based, and then the video work is time-based, but the photographs also seem to me to be very concerned to articulate an experience of time. And so the way in which space is articulated in the images seems to give you a sense of the time of your looking at the image - and a sense of time within the construction of the image itself.

DH: Yes. I'm happy that you understand this in my work. Because it is so central to my interests. One thing that I'd say, one of the things that sort of lured me out of time–based media was time (laughs). How different is the time of the moving and still images. I did a project, People in Buildings (1989), which is a two-channel projected video installation that creates faux architectural exteriors pastiched out of bits of existing architecture, video snow, all kind of things, creating a post-modern architectural façade of media. The viewer walks through a doorway in this facade and approaches a second projection. It shows people in various instances of looking or waiting. Shot in libraries you see people reading or searching through the stacks; in a porno shop men thumbing through magazines; in the emergency room of a hospital sick and injured people waiting to be seen; or in a small boutique women caressing the clothing. All this looking, desiring, waiting. People hoping for something to happen.

While I was shooting People in Buildings, I spent a lot of time in different kinds of institutional spaces. Around this time, the summer of 1989, I began fooling around with large format photography and decided to return to some of those spaces so I could photograph their long institutional corridors. Without fully understanding why, I knew that I wanted to stop time. There was something about the sequential nature of video time that seemed to be getting in the way. I am not sure of what. Or at least I wasn't sure then. Like a leaf dropped into a stream images pass by; are here and then just as quickly are gone. The photographic image is a lot more patient. It sticks around. Time is brought to a standstill. Or at least it appears that way. At the very least we can probably agree that the image at a standstill offers a different kind of sustained scrutiny than is possible for, or even the intention of, moving images.

This kind of looking that certain photographs allow (well, all photos allow but which only some take advantage of) what I have called deep recognition. I am trying to describe the way one's imagination dances across and through some photographs, alighting here and there. The photograph maintains its references but in some instances (and I think this is one of the things that separates a good photo from a not-so-good one) it seems to become disconnected, set adrift from the world as fact. It becomes a dream image that we meander into at our own speed. In this sense the image is allegorical. Providing a degree of scrutiny and detail that's impossible for the unaided eye, it is beyond real; not real at all and surely not true. It is at this moment when the photograph abandons any claims of accurately describing the world that it assumes its more important role of describing ourselves. This deep recognition then is a self-recognition.

Q: Because, again, that's to do with the notion that everything is constructed, including one's experience of time.

DH: We construct meaning, whether one is an artist or not. We are constructing meaning constantly out of the fragments that populate our everyday lives. I think that one of the things that art does well is foreground this process.

Q: One of the things that's really interesting to me is that you kind of arrive at a point with the photographs where they're completely in focus at every point. They are of large scale and they relate to notions of landscape and portraiture and film -

DH: Which is very familiar.

Q: And by adhering more and more closely to these things they interrogate the way you experience these points of reference and become different from the images they incorporate.

DH: I'd like that to be the case. I'm not sure it's always the case, but that's certainly what motivates me. That's the rationale.

Q: And it is not unrelated to being artist in residence at the television station.

DH: Yeah, it's totally related. I'm glad you see that (laughter), because most people don't.

Q: To me it is so interesting because there's an implicit notion of your occupation of a site at every stage in your work, but you're inflecting the notion of site in different ways at different times. Can I ask you about the installation we've just seen - Chrysopylae? (2012) - because that's going back to a medium which controls the time. Yet I don't think that when you experience the installation you feel that there's the leaf going down the stream in this determined way.

Doug Hall, Chrysopylae, 2 channel projected video installation, installation view, Fort Point, San Francisco, 2012. Courtesy: Doug Hall.

DH: Well, maybe that's a difference caused by the space of media installation, which for the most part doesn't settle the viewer into a safe, fixed point but sets her somewhat adrift within the setting. Not only are the images on the screens in motion but often one's body is as well so perhaps the viewer takes on some of the attributes of the leaf caught in the swirls and eddies of images and time. In Chrysopylae it's a pretty visceral sensation of media. It's about bridges and ships, commerce, and time. The images are large and the complex sound track with its deep, resonant undertones is extremely physical. The experience is, I think, satisfying but its overwhelming nature is also a little bit threatening. I think that media brings us certain gifts (ways of seeing and understanding), but I also think that there's a price to be paid. It's extremely manipulative. I think there's a degree of terror in it all. What I have called the terror of mediation. Maybe this is generational and wouldn't be true for somebody much younger who has spent his whole life consuming and consumed by media. And by terror I don't mean that it's something that we necessarily shy away from. In fact, I think there can be a profound pleasure in all of it. We crave sensation.

Also, the content in Chrysopylae is satisfying: the bridge; the ships; the changing light over the course of a day. Everything is so present, so massive and physical. And it is shot so that events appear to unfold. And because I shot everything with two cameras in parallel and in sync, one for each screen, I was able to make these huge two-screen panoramas that I could then intervene into.

Q: I think the other aspect is because of the pace of it and the dual screens. There is, again, this tremendous sense of the articulation of space and that means that you become aware that you're calibrating your time in relation to the time of the edit. So you have this duality that makes it an installation not just because it is an installation but because you're articulating the times in the installation.

DH: That's a good point. Although there's very little camera movement, there is a tremendous amount of movement in and between the dual screens. And the scale of the screens is quite large at 12 feet by 7; times two with a 6 inch gap you are looking at scenes that are almost 25 feet across. The viewer is aware of the stereoscopic effect and of the gap that separates the two sides. I occasionally intervene into the coherent time of the two screens and break the flow between them, which I think (I hope) makes one aware, perhaps unconsciously, of the temporal issues, and maybe also of the spatial issues you are referring to. I think too that one becomes conscious of the edges; about how scenes come in and out of the picture plane; what these framing devices both include and exclude.

Q: There was a very interesting moment for me when the ship was smaller and went up to the top right-hand corner, and I had this sense that the corner was going to extend.

DH: Yeah, exactly.

Q: You could see the whole ship. And I don't know whether it was slowing down in time, but I had this rather curious experience that the frame itself was growing.

DH: That Chrysopylae worked out as well as it did is as much a mystery to me (laughs) as anyone.